26. PUNCAK

Another new school term found me filled with energy and enthusiasm. Honestly. But after the first five days of teaching it was good to escape, on the Saturday, from the oily traffic of Jakarta to the balmy hills beyond Bogor. Beneath a sky of tropical blue I motored up from Bogor towards the nearby Puncak Pass. I was hoping to find an interesting track that would lead me to some lost domain. Somewhere between the towns of Ciawi and Cisarua I found what I was looking for, although I don’t think I would ever be able to find the exact same spot again.

My path wandered through fields of sweet-smelling green papaya; it skirted rice paddies where muddy boys rode gentle water buffaloes; there was a primary school with a red and white flag and marching children; goats and ducks led me through a kampung where the houses had muddy brick and plaster walls, loose red tiles and gardens of jasmine; the children wore bright green sarongs.

I entered an area of dark shadows and spiky leaves. I passed beneath jackfruit, rambutan and durian, and squeezed through a tangle of lianas and bamboos. Help! I was in the middle of nowhere.

"Hello mister," said a lad, half way up a tree, collecting fruit. He was about thirteen years of age, dressed in clean blue school shorts and expensive-looking T-shirt, and had a happy and handsome Sundanese face.

"Hello," I said, relieved to find the voice came from a human. "Is there a restaurant near here?"

"There’s a hotel," said the lad beginning to climb down. He was followed by a younger boy wearing a mischievous smile and red school shorts and an older girl wearing a tight yellow blouse and tight jeans.

"How do I get there?" I asked.

"We’ll take you," said the older boy, scratching various insect bites.

"Thanks. What’s your name?"

"I’m Dede," said the older boy, "and this is my younger brother, Agus, and my sister, Melati."

"I’m Diego Maradona," I explained.

"The singer?" said Dede.

"No actually I’m Woody Allen," I said.

"Where are you from Mr Woody?" asked Dede, who apparently knew less about films than music.

"Jakarta."

"You want a place to stay?" asked Melati, who had lovely eyes and lips.

"No, just something to eat. Is it a good hotel?"

"Lots of girls there," piped up Agus, eyes sparkling.

"How do you mean?"

"Lots of women," said Melati, looking at Agus and giggling.

"You like drugs?" asked Dede.

"No. Definitely not. What kind of hotel is it?"

"They tried to burn it down," explained Dede.

"Who did?"

"A mob," said Dede.

"Why?"

"Some people round here don’t like these places," said Melati.

"Who owns it?"

"Chinese," said Dede.

"They didn’t manage to burn it down?"

"No. There were too many police and soldiers," said Dede.

"I think I’ll get something to eat at a roadside stall. Can you show me the way?"

"Certainly," said Dede, as he handed me some rambutan.

As we followed a narrow path through the woodland, I was thinking how good it was to still be able to find trees on the island of Java. Ninety percent of the island’s original forests have been cut down.

"Do you have any Gharu trees?" I asked. I had heard that such trees were to be found in western New Guinea and that the resin from the trees could be used as a drug to help you contact your ancestors.

Melati shook her head and looked puzzled.

"Left or right?" I asked, as we emerged from the dark and reached an area of rough grassland and scattered trees.

"Not left," said Dede.

"Ghosts on the left," said Agus, steering us to the right.

"Really?" I asked.

"An old man died near here," said Dede.

"What happened?" I said, noting the sober expressions on the faces of the two boys.

"People said he used black magic. He died suddenly," explained Agus.

"He was a dukun jilat," said Melati.

"What kind of dukun is that?" I asked.

Dede made sucking sounds with his mouth. "The dukun sucks the bit of you that’s sakit," he said, while scratching himself.

"Black magic?" I said.

"Some babies got sick," said Melati.

"The old man had some land," said Dede.

"A rich man from Jakarta now has the land," said Melati.

A red tiled school building came into view.

"My school," said Agus.

"Can I have a look?" I said.

Agus happily led us into the empty building which was made up of a handful of classrooms around a courtyard. I noted the rotting timbers, the graffiti on walls, and the complete absence of any kind of equipment or furniture other than cheap wooden desks with names carved on them.

Agus took a thick pen from his pocket and began to apply some scribbles to an exterior wall.

"I think we’d better move on," I said.

A small shop at a road junction provided a place for me to buy my meal of bananas, biscuits and cola. Mysteriously enough I could see my vehicle parked a few metres down the street. Before departing, I rewarded my guides.

"Thank you, Woody Allen," said Dede.

..

..

Chong, the malnourished young man I had found lying in the street and taken to the mental hospital at Babakan in Bogor, hadn’t been visited by me for some time; so to assuage my guilt I went to see him.

I strode through the hospital’s sunny gardens, admiring the white Gardenia, the red and yellow Rangoon Creeper, and the handsome, modern two storey block containing the director’s office; finally, some distance from the hospital entrance, I reached the warehouse-like ward housing Chong.

"I’ve come to take Chong for a walk," I said to the young male nurse who opened the locked door of the mildewed building.

"Chong?" The nurse, casually dressed in T-shirt and jeans, looked as if he had never heard the name before.

"Yes, please."

He went inside to check.

"Nobody here called Chong," said the nurse on his return.

"There must be. I brought him to this hospital and he was in this ward last time I visited."

"He’s not here."

"Are you absolutely sure?"

"Yes. I know all the patients."

"Do you remember Chong?"

"No," he said, with a sort of vacant grin.

"I’ll go to the Director’s office and ask there." I felt ready to lash my tail.

I explained the situation to the director’s secretary, who informed me that the director was away in Jakarta, but that I could speak to a deputy. I was eventually introduced to a round-faced doctor with thinning hair and a sharp looking man wearing an expensive suit and tinted glasses.

"We’ve sent someone to collect Chong," said the doctor, sitting back on the expensive black leather settee.

"Would you like some tea?" asked the man with the smart suit.

"No thanks," I answered politely.

A nurse entered with a young male patient who had broad shoulders and a grinning Javanese face.

"Here’s Chong," said the doctor.

"This is not Chong," I said. "Chong looks Chinese and he’s slim."

"This is Chong," said the smiling nurse.

"It’s not the person I brought to the hospital."

There was a period of silence.

"Have you tried the mental hospital on Jalan Dr Semeru?" volunteered the nurse.

"That’s not where I took Chong," I said.

"I’m sorry we can’t help you," said the doctor.

"Have you checked the records?" I asked.

"We have," said the unruffled doctor.

"What do you think has happened to Chong?"

"The only Chong we have is this man the nurse brought here."

"But he is not Chong," I said.

"Mr Kent, I’m sorry we can’t help you," said the man with the tinted glasses.

I supposed there was nothing I could do. It was possible that Chong had been allowed out of his ward and had wandered through the gardens and subsequently through the hospital’s open gates. There was no great incentive to keep a careful eye on a patient like Chong; I had not visited Chong for some time and his family had no interest in him. Perhaps he had got sick and died; perhaps he was wandering through the streets of Bogor.

Later that morning, while taking a walk alongside the Ciliwung river, not far from Bogor’s botanic gardens, I spotted a ragged-looking figure under a wide stone bridge. Could it be Chong? I crossed a patch of tall grass to have a closer look.

Instead of Chong I found a teenage boy, a granny, a small girl, a few pots and pans, several sleeping mats and some plastic bags: a home under a bridge.

"Hello," I said, being careful not to go too close. I didn’t want to actually enter their bedroom.

They stared at me with frightened eyes. Or was it hostility?

"Do you live here, under the bridge?" I asked.

The boy nodded.

"How many people?"

"Five," said the granny, who managed a slight smile.

"Do you work in Bogor?"

"In the market," she said.

I took some money from my pocket and held my hand out in their direction. The boy took it, almost grabbing it.

"Thank you," said the granny.

Leaving the centre of Bogor, I motored along the usual bumpy roads to Bogor Baru. Having visited little Andi and tubercular Asep, who seemed in reasonable health, I decided to find out how Ciah was getting on. Ciah was sitting on her verandah, looking pale but reasonably well recovered from her hepatitis. Maybe her lack of colour was due to the lichen and moss covered trees cutting off the sun from her shack.

"How’s Agosto?" I asked.

"He’s sick," said Ciah, standing up and beckoning me into the wood and bamboo house.

Lying on the black metal bed, which almost filled the stuffy room, was twelve-year-old Agosto. He looked fevered, withered and yellowy-green.

Two neighbours, having helped carry the boy down to the road and into the back of my van, accompanied us to the Menteng Hospital. I wondered if we would get there in time to save him. He closed his eyes but kept on breathing all the way through town.

We reached the emergency ward and Agosto was laid on a bed covered in stained plastic.

"How long has he been ill?" asked the young doctor.

"I think it’s about ten days," said Ciah in a tired voice.

"Cough?"

"Yes," said Ciah. Agosto seemed to be not quite aware of what was going on.

"Headache?"

"Yes."

"Stomach pain?"

"Yes."

"Constipation or diarrhoea?"

"Yes," said Ciah, sounding hesitant.

I got the feeling she was not too clear in her thinking.

The doctor looked at a rash on Agosto’s abdomen and peered down his throat. A nurse took his temperature, did a blood test and attached him to a drip.

"What do you think it is?" I asked the doctor.

"Typhoid, probably. Very common among children aged ten to fourteen. It can take several tests to be sure. Not easy to diagnose. We’ll give him antibiotics."

"Is he very seriously ill?" I said.

"It’s a pity Agosto wasn’t brought here much earlier," said the doctor frowning, "He’s very dehydrated and weak."

"Do you think he’s going to be OK?"

"We hope so. There’s always a risk of complications, especially when patients get here late."

"What kind of complications?"

"Meningitis, intestinal bleeding, pneumonia. There’s a problem if the infection gets into the bloodstream and moves to the liver."

"Why do so many kids get typhoid?" I asked.

"Patients who’ve recovered can still be carriers. The bacteria is in their faeces. So it spreads. Dirty food and dirty water."

"Kids don’t wash their hands?" I said.

"And food has to be boiled for twelve minutes to kill any bacteria in it."

"Why don’t kids get vaccinated?"

"Vaccination can cost a month’s wages and it only covers you for three years. Another problem is that some antibiotics don’t work anymore." The doctor gave a shrug and a friendly smile before heading to a desk to do some paperwork.

Agosto was wheeled through a section of garden and into the crowded third class children’s ward, a long shed-like building with big metal windows. Sitting beside the sick children were family members who had brought with them baskets of home made snacks and bottles of tea. In one corner of the ward, a mother and daughter guarded a little girl who was even more grey and wizened than Agosto.

"Who’s the girl in the corner bed?" I asked the nurse, as she adjusted Agosto’s drip.

"Suhartini."

"She’s not on a drip," I said.

"The parents are very poor," explained the nurse.

"Is she getting any medicine?"

"They can’t afford it," said the nurse.

"What’s wrong with Suhartini?" I asked.

"Typhoid. And there are complications."

I looked at Suhartini’s mother and older sister who were seated at the bedside. The tired looking mother wore a watch, although it may have been of little value. The older sister looked plump and wore a clean school uniform.

"I’ll pay for the medicine," I said to the nurse. "Has the mother got the prescription?"

"Yes, you can take it to the pharmacy near the entrance."

This was explained to the mother and I was accompanied to the chemist by the plump sister.

"How many days will Suhartini’s medicine last?" I asked the pharmacist.

"Three days."

"Can the doctor write out a prescription to last more than three days? I live in Jakarta and can’t get here every day."

"No," said the pharmacist. "The family must buy more medicine in three days time."

"I’ll need to give the mother some money for that," I said.

"Give me money for school," said the grinning sister. She seemed to show no trace of anxiety about her sibling, but then emotions are often difficult to detect.

Back at the children’s ward, I handed over some money to Ciah and to Suhartini’s mum.

"For medicine and food only," I said. "Not for other things."

My path wandered through fields of sweet-smelling green papaya; it skirted rice paddies where muddy boys rode gentle water buffaloes; there was a primary school with a red and white flag and marching children; goats and ducks led me through a kampung where the houses had muddy brick and plaster walls, loose red tiles and gardens of jasmine; the children wore bright green sarongs.

I entered an area of dark shadows and spiky leaves. I passed beneath jackfruit, rambutan and durian, and squeezed through a tangle of lianas and bamboos. Help! I was in the middle of nowhere.

"Hello mister," said a lad, half way up a tree, collecting fruit. He was about thirteen years of age, dressed in clean blue school shorts and expensive-looking T-shirt, and had a happy and handsome Sundanese face.

"Hello," I said, relieved to find the voice came from a human. "Is there a restaurant near here?"

"There’s a hotel," said the lad beginning to climb down. He was followed by a younger boy wearing a mischievous smile and red school shorts and an older girl wearing a tight yellow blouse and tight jeans.

"How do I get there?" I asked.

"We’ll take you," said the older boy, scratching various insect bites.

"Thanks. What’s your name?"

"I’m Dede," said the older boy, "and this is my younger brother, Agus, and my sister, Melati."

"I’m Diego Maradona," I explained.

"The singer?" said Dede.

"No actually I’m Woody Allen," I said.

"Where are you from Mr Woody?" asked Dede, who apparently knew less about films than music.

"Jakarta."

"You want a place to stay?" asked Melati, who had lovely eyes and lips.

"No, just something to eat. Is it a good hotel?"

"Lots of girls there," piped up Agus, eyes sparkling.

"How do you mean?"

"Lots of women," said Melati, looking at Agus and giggling.

"You like drugs?" asked Dede.

"No. Definitely not. What kind of hotel is it?"

"They tried to burn it down," explained Dede.

"Who did?"

"A mob," said Dede.

"Why?"

"Some people round here don’t like these places," said Melati.

"Who owns it?"

"Chinese," said Dede.

"They didn’t manage to burn it down?"

"No. There were too many police and soldiers," said Dede.

"I think I’ll get something to eat at a roadside stall. Can you show me the way?"

"Certainly," said Dede, as he handed me some rambutan.

As we followed a narrow path through the woodland, I was thinking how good it was to still be able to find trees on the island of Java. Ninety percent of the island’s original forests have been cut down.

"Do you have any Gharu trees?" I asked. I had heard that such trees were to be found in western New Guinea and that the resin from the trees could be used as a drug to help you contact your ancestors.

Melati shook her head and looked puzzled.

"Left or right?" I asked, as we emerged from the dark and reached an area of rough grassland and scattered trees.

"Not left," said Dede.

"Ghosts on the left," said Agus, steering us to the right.

"Really?" I asked.

"An old man died near here," said Dede.

"What happened?" I said, noting the sober expressions on the faces of the two boys.

"People said he used black magic. He died suddenly," explained Agus.

"He was a dukun jilat," said Melati.

"What kind of dukun is that?" I asked.

Dede made sucking sounds with his mouth. "The dukun sucks the bit of you that’s sakit," he said, while scratching himself.

"Black magic?" I said.

"Some babies got sick," said Melati.

"The old man had some land," said Dede.

"A rich man from Jakarta now has the land," said Melati.

A red tiled school building came into view.

"My school," said Agus.

"Can I have a look?" I said.

Agus happily led us into the empty building which was made up of a handful of classrooms around a courtyard. I noted the rotting timbers, the graffiti on walls, and the complete absence of any kind of equipment or furniture other than cheap wooden desks with names carved on them.

Agus took a thick pen from his pocket and began to apply some scribbles to an exterior wall.

"I think we’d better move on," I said.

A small shop at a road junction provided a place for me to buy my meal of bananas, biscuits and cola. Mysteriously enough I could see my vehicle parked a few metres down the street. Before departing, I rewarded my guides.

"Thank you, Woody Allen," said Dede.

..

..Chong, the malnourished young man I had found lying in the street and taken to the mental hospital at Babakan in Bogor, hadn’t been visited by me for some time; so to assuage my guilt I went to see him.

I strode through the hospital’s sunny gardens, admiring the white Gardenia, the red and yellow Rangoon Creeper, and the handsome, modern two storey block containing the director’s office; finally, some distance from the hospital entrance, I reached the warehouse-like ward housing Chong.

"I’ve come to take Chong for a walk," I said to the young male nurse who opened the locked door of the mildewed building.

"Chong?" The nurse, casually dressed in T-shirt and jeans, looked as if he had never heard the name before.

"Yes, please."

He went inside to check.

"Nobody here called Chong," said the nurse on his return.

"There must be. I brought him to this hospital and he was in this ward last time I visited."

"He’s not here."

"Are you absolutely sure?"

"Yes. I know all the patients."

"Do you remember Chong?"

"No," he said, with a sort of vacant grin.

"I’ll go to the Director’s office and ask there." I felt ready to lash my tail.

I explained the situation to the director’s secretary, who informed me that the director was away in Jakarta, but that I could speak to a deputy. I was eventually introduced to a round-faced doctor with thinning hair and a sharp looking man wearing an expensive suit and tinted glasses.

"We’ve sent someone to collect Chong," said the doctor, sitting back on the expensive black leather settee.

"Would you like some tea?" asked the man with the smart suit.

"No thanks," I answered politely.

A nurse entered with a young male patient who had broad shoulders and a grinning Javanese face.

"Here’s Chong," said the doctor.

"This is not Chong," I said. "Chong looks Chinese and he’s slim."

"This is Chong," said the smiling nurse.

"It’s not the person I brought to the hospital."

There was a period of silence.

"Have you tried the mental hospital on Jalan Dr Semeru?" volunteered the nurse.

"That’s not where I took Chong," I said.

"I’m sorry we can’t help you," said the doctor.

"Have you checked the records?" I asked.

"We have," said the unruffled doctor.

"What do you think has happened to Chong?"

"The only Chong we have is this man the nurse brought here."

"But he is not Chong," I said.

"Mr Kent, I’m sorry we can’t help you," said the man with the tinted glasses.

I supposed there was nothing I could do. It was possible that Chong had been allowed out of his ward and had wandered through the gardens and subsequently through the hospital’s open gates. There was no great incentive to keep a careful eye on a patient like Chong; I had not visited Chong for some time and his family had no interest in him. Perhaps he had got sick and died; perhaps he was wandering through the streets of Bogor.

Later that morning, while taking a walk alongside the Ciliwung river, not far from Bogor’s botanic gardens, I spotted a ragged-looking figure under a wide stone bridge. Could it be Chong? I crossed a patch of tall grass to have a closer look.

Instead of Chong I found a teenage boy, a granny, a small girl, a few pots and pans, several sleeping mats and some plastic bags: a home under a bridge.

"Hello," I said, being careful not to go too close. I didn’t want to actually enter their bedroom.

They stared at me with frightened eyes. Or was it hostility?

"Do you live here, under the bridge?" I asked.

The boy nodded.

"How many people?"

"Five," said the granny, who managed a slight smile.

"Do you work in Bogor?"

"In the market," she said.

I took some money from my pocket and held my hand out in their direction. The boy took it, almost grabbing it.

"Thank you," said the granny.

Leaving the centre of Bogor, I motored along the usual bumpy roads to Bogor Baru. Having visited little Andi and tubercular Asep, who seemed in reasonable health, I decided to find out how Ciah was getting on. Ciah was sitting on her verandah, looking pale but reasonably well recovered from her hepatitis. Maybe her lack of colour was due to the lichen and moss covered trees cutting off the sun from her shack.

"How’s Agosto?" I asked.

"He’s sick," said Ciah, standing up and beckoning me into the wood and bamboo house.

Lying on the black metal bed, which almost filled the stuffy room, was twelve-year-old Agosto. He looked fevered, withered and yellowy-green.

Two neighbours, having helped carry the boy down to the road and into the back of my van, accompanied us to the Menteng Hospital. I wondered if we would get there in time to save him. He closed his eyes but kept on breathing all the way through town.

We reached the emergency ward and Agosto was laid on a bed covered in stained plastic.

"How long has he been ill?" asked the young doctor.

"I think it’s about ten days," said Ciah in a tired voice.

"Cough?"

"Yes," said Ciah. Agosto seemed to be not quite aware of what was going on.

"Headache?"

"Yes."

"Stomach pain?"

"Yes."

"Constipation or diarrhoea?"

"Yes," said Ciah, sounding hesitant.

I got the feeling she was not too clear in her thinking.

The doctor looked at a rash on Agosto’s abdomen and peered down his throat. A nurse took his temperature, did a blood test and attached him to a drip.

"What do you think it is?" I asked the doctor.

"Typhoid, probably. Very common among children aged ten to fourteen. It can take several tests to be sure. Not easy to diagnose. We’ll give him antibiotics."

"Is he very seriously ill?" I said.

"It’s a pity Agosto wasn’t brought here much earlier," said the doctor frowning, "He’s very dehydrated and weak."

"Do you think he’s going to be OK?"

"We hope so. There’s always a risk of complications, especially when patients get here late."

"What kind of complications?"

"Meningitis, intestinal bleeding, pneumonia. There’s a problem if the infection gets into the bloodstream and moves to the liver."

"Why do so many kids get typhoid?" I asked.

"Patients who’ve recovered can still be carriers. The bacteria is in their faeces. So it spreads. Dirty food and dirty water."

"Kids don’t wash their hands?" I said.

"And food has to be boiled for twelve minutes to kill any bacteria in it."

"Why don’t kids get vaccinated?"

"Vaccination can cost a month’s wages and it only covers you for three years. Another problem is that some antibiotics don’t work anymore." The doctor gave a shrug and a friendly smile before heading to a desk to do some paperwork.

Agosto was wheeled through a section of garden and into the crowded third class children’s ward, a long shed-like building with big metal windows. Sitting beside the sick children were family members who had brought with them baskets of home made snacks and bottles of tea. In one corner of the ward, a mother and daughter guarded a little girl who was even more grey and wizened than Agosto.

"Who’s the girl in the corner bed?" I asked the nurse, as she adjusted Agosto’s drip.

"Suhartini."

"She’s not on a drip," I said.

"The parents are very poor," explained the nurse.

"Is she getting any medicine?"

"They can’t afford it," said the nurse.

"What’s wrong with Suhartini?" I asked.

"Typhoid. And there are complications."

I looked at Suhartini’s mother and older sister who were seated at the bedside. The tired looking mother wore a watch, although it may have been of little value. The older sister looked plump and wore a clean school uniform.

"I’ll pay for the medicine," I said to the nurse. "Has the mother got the prescription?"

"Yes, you can take it to the pharmacy near the entrance."

This was explained to the mother and I was accompanied to the chemist by the plump sister.

"How many days will Suhartini’s medicine last?" I asked the pharmacist.

"Three days."

"Can the doctor write out a prescription to last more than three days? I live in Jakarta and can’t get here every day."

"No," said the pharmacist. "The family must buy more medicine in three days time."

"I’ll need to give the mother some money for that," I said.

"Give me money for school," said the grinning sister. She seemed to show no trace of anxiety about her sibling, but then emotions are often difficult to detect.

Back at the children’s ward, I handed over some money to Ciah and to Suhartini’s mum.

"For medicine and food only," I said. "Not for other things."

27. A GIRLFRIEND AGED SIXTEEN

After seven days, I returned to the third-class children’s ward of the Menteng Hospital in Bogor. In the simple sunlit room, there was a smell of unwashed bare feet and sweaty anxiety. I was feeling jittery; almost reluctant to look at anyone’s face. But I could see Agosto; he was still alive. In fact, although he still looked a bit shrivelled, he was reasonably alert and able to sit up. Ciah, his mother, was smiling a wan smile.

"His fever’s down," said the nurse, a pleasant, plump, matronly woman. "Now he needs to put on weight."

"How’s Suhartini?" I asked. The little girl’s bed was occupied by a new patient, a cheerful boy.

"Gone," said the nurse, in a soft voice.

"What happened?" I asked, my heart beginning to beat faster.

"No longer here," said the nurse, soothingly.

"Dead?" I asked, in a louder voice.

"She’s left this world," said the nurse, putting on a little smile.

Other visitors were looking in my direction and also smiling. It was that smile that tries to lessen the impact of bad news.

My stomach tightened. I wondered if she would have survived if she had got her typhoid medicine a bit sooner. It seemed criminal that when she had first arrived at the hospital she had apparently not been given any medicine.

"The government’s supposed to give hospitals money," I said to the nurse, with more than a hint of rage. "For free medicine; for the very poor."

"People have to pay," said the nurse quietly.

"Does this hospital get money from the government?" I asked, determined to press my point.

"The money runs out very quickly," said the nurse, giving me a smile with a hint of cynicism.

"I’ll give you my telephone number," I said to the nurse. "Phone me if there’s another case like Suhartini."

She never did phone.

After leaving the Menteng Hospital I returned to the Bogor district of Babakan. I had stuck Chong’s photo to a piece of paper, added my telephone number and a sentence about a reward being offered for his safe return, made lots of photocopies, and brought them to the mental hospital.

"Has Chong been found yet?" I asked the grey little man in the mental hospital’s dusty front-office.

"Chong?" he said. He wore a puzzled expression. Or was it boredom?

I explained about Chong. "I’ve made this poster," I said. "May I give them out to people?"

"Yes." His face had become expressionless.

In the open-air market area just north of the railway station I distributed my photocopies, mainly to resting pedicab drivers. Nobody who looked at the poster recognised the face or seemed particularly interested. I didn’t want to stay too long in case someone in authority asked me what on earth I was doing. You probably need permission in triplicate before giving out leaflets.

Weeks passed but there was no word of Chong. He had vanished; and I would never see him again.

The school term moved on and the rainy season arrived early. On a Saturday morning of black skies I made my daily check-up on Min at his home in South Jakarta. As I stepped into the little front room, Min got up from the frayed and stained settee and began dancing around and sort of singing. He was having one of his hyperactive days. I wondered if his more eccentric behaviour was related to his illness at age seven, which was presumably something like meningitis or encephalitis, or related to the poverty of his early environment, or related to something inherited. Probably it was a combination of factors.

"Kent," said Wati, Min’s mum, who was wearing her best batik dress, "Aldi’s now going to school here in Cipete."

"Great," I said.

It was good to hear that the middle child in the family, eleven-year-old Aldi, was now living in the new house, rather than back in the slums of North Jakarta. Aldi, looking handsome but not wildly happy, appeared at the kitchen door. He was frowning, but I presumed he was going to be able to settle-in and make new friends.

"Kent," continued Wati, in a begging voice, "Min’s relatives in Cengkareng. We’d like to visit them. Can you take us?"

"Cengkareng?"

"It’s near Min’s old house in Teluk Gong. Near the sea."

"I want to go to Teluk Gong," I said, "to visit Sani and Indra, the seven-year-olds with TB. So we can go to Cengkareng after that."

We trooped out of the house, me, Min, Min’s mum and dad, Wardi, eleven-year-old Aldi, and little Itin and Imah. In single file, and watched by the neighbours, we paraded down the street towards my vehicle.

It was raining heavily as we made the one and a half hour journey to North Jakarta through the more than usually jammed streets.

The area around Min’s old house looked different. Due to the heavy rains, and the high tide, it was under water. About two feet under water. There was a canoe sailing down the main street and happy kids in bathing costumes were swimming past the doctor’s clinic. Some citizens had moved furniture onto their roofs. We had to park the Mitsubishi on the higher ground at the entrance to the area.

"How do we get through here?" I asked.

"Motorbikes," said Wardi. "We can get ojeks."

The ojek drivers were doing a roaring trade. Wardi and Min got on the back of one bike and I got on the back of another. I kept my feet as high as possible as we drove along the Venice-like lanes to the wooden house on stilts occupied by little Sani and Indra. We didn’t hit too many deep potholes and we didn’t topple over.

"How are Sani and Indra?" I asked their mum, who was standing at her door. In fact I could see the two children and they were as puny and sickly as before.

"OK," said mum, wearing a vacant look.

"They’re twins, Sani and Indra," explained Wardi.

"Are they eating well?" I asked.

"No," said mum.

"Have they still got coughs?"

"Yes."

"Is the medicine finished?"

"No."

"Can I have a look?" I said, while stepping inside the house.

"His fever’s down," said the nurse, a pleasant, plump, matronly woman. "Now he needs to put on weight."

"How’s Suhartini?" I asked. The little girl’s bed was occupied by a new patient, a cheerful boy.

"Gone," said the nurse, in a soft voice.

"What happened?" I asked, my heart beginning to beat faster.

"No longer here," said the nurse, soothingly.

"Dead?" I asked, in a louder voice.

"She’s left this world," said the nurse, putting on a little smile.

Other visitors were looking in my direction and also smiling. It was that smile that tries to lessen the impact of bad news.

My stomach tightened. I wondered if she would have survived if she had got her typhoid medicine a bit sooner. It seemed criminal that when she had first arrived at the hospital she had apparently not been given any medicine.

"The government’s supposed to give hospitals money," I said to the nurse, with more than a hint of rage. "For free medicine; for the very poor."

"People have to pay," said the nurse quietly.

"Does this hospital get money from the government?" I asked, determined to press my point.

"The money runs out very quickly," said the nurse, giving me a smile with a hint of cynicism.

"I’ll give you my telephone number," I said to the nurse. "Phone me if there’s another case like Suhartini."

She never did phone.

After leaving the Menteng Hospital I returned to the Bogor district of Babakan. I had stuck Chong’s photo to a piece of paper, added my telephone number and a sentence about a reward being offered for his safe return, made lots of photocopies, and brought them to the mental hospital.

"Has Chong been found yet?" I asked the grey little man in the mental hospital’s dusty front-office.

"Chong?" he said. He wore a puzzled expression. Or was it boredom?

I explained about Chong. "I’ve made this poster," I said. "May I give them out to people?"

"Yes." His face had become expressionless.

In the open-air market area just north of the railway station I distributed my photocopies, mainly to resting pedicab drivers. Nobody who looked at the poster recognised the face or seemed particularly interested. I didn’t want to stay too long in case someone in authority asked me what on earth I was doing. You probably need permission in triplicate before giving out leaflets.

Weeks passed but there was no word of Chong. He had vanished; and I would never see him again.

The school term moved on and the rainy season arrived early. On a Saturday morning of black skies I made my daily check-up on Min at his home in South Jakarta. As I stepped into the little front room, Min got up from the frayed and stained settee and began dancing around and sort of singing. He was having one of his hyperactive days. I wondered if his more eccentric behaviour was related to his illness at age seven, which was presumably something like meningitis or encephalitis, or related to the poverty of his early environment, or related to something inherited. Probably it was a combination of factors.

"Kent," said Wati, Min’s mum, who was wearing her best batik dress, "Aldi’s now going to school here in Cipete."

"Great," I said.

It was good to hear that the middle child in the family, eleven-year-old Aldi, was now living in the new house, rather than back in the slums of North Jakarta. Aldi, looking handsome but not wildly happy, appeared at the kitchen door. He was frowning, but I presumed he was going to be able to settle-in and make new friends.

"Kent," continued Wati, in a begging voice, "Min’s relatives in Cengkareng. We’d like to visit them. Can you take us?"

"Cengkareng?"

"It’s near Min’s old house in Teluk Gong. Near the sea."

"I want to go to Teluk Gong," I said, "to visit Sani and Indra, the seven-year-olds with TB. So we can go to Cengkareng after that."

We trooped out of the house, me, Min, Min’s mum and dad, Wardi, eleven-year-old Aldi, and little Itin and Imah. In single file, and watched by the neighbours, we paraded down the street towards my vehicle.

It was raining heavily as we made the one and a half hour journey to North Jakarta through the more than usually jammed streets.

The area around Min’s old house looked different. Due to the heavy rains, and the high tide, it was under water. About two feet under water. There was a canoe sailing down the main street and happy kids in bathing costumes were swimming past the doctor’s clinic. Some citizens had moved furniture onto their roofs. We had to park the Mitsubishi on the higher ground at the entrance to the area.

"How do we get through here?" I asked.

"Motorbikes," said Wardi. "We can get ojeks."

The ojek drivers were doing a roaring trade. Wardi and Min got on the back of one bike and I got on the back of another. I kept my feet as high as possible as we drove along the Venice-like lanes to the wooden house on stilts occupied by little Sani and Indra. We didn’t hit too many deep potholes and we didn’t topple over.

"How are Sani and Indra?" I asked their mum, who was standing at her door. In fact I could see the two children and they were as puny and sickly as before.

"OK," said mum, wearing a vacant look.

"They’re twins, Sani and Indra," explained Wardi.

"Are they eating well?" I asked.

"No," said mum.

"Have they still got coughs?"

"Yes."

"Is the medicine finished?"

"No."

"Can I have a look?" I said, while stepping inside the house.

She hesitated. I could see the bed, and two shelves. There really wasn’t much else. On one shelf was a clear plastic bag and in the bag were the clear plastic cartons containing the TB pills. I pointed to the bag and she brought it over for me to have a look.

"The medicine cartons haven’t been opened since you got them from the hospital," I pointed out.

"Yes they have," she said.

"Look, the cartons are full to the brim. Have you been forgetting to give the kids their medicine?"

"No." She looked away.

"Have you got a calendar where you can tick off the medicine each day?"

"No."

I took a page from my notebook and made a simple calendar.

"My driver will come here next week to check you’ve remembered to give them their pills. They must get them every day. Are you going to forget tomorrow?"

"No."

Before leaving, I watched her give that day’s medicine to the twins and watched her tick off the date.

Leaving Teluk Gong, we drove East towards Cengkareng along minor roads that in places were about a foot under water.

"Look at those houses," said Wardi pointing leftwards to a middle class housing estate where flood water had reached window height. "These were only built a few years ago."

"They’ve cut down too many trees up in the Puncak," I said. "Instead of the trees they’ve got luxury houses and golf courses designed by these top name golfers from America."

"Yeah," said Wardi, looking blank.

"When it rains," I continued, "the water goes too quickly into the rivers. No trees to slow down the water. The rivers and drainage channels overflow their banks and Jakarta gets flooded. Friends of the President have taken over entire hills near Bogor."

"This area’s always flooding," said Wardi.

"If they’d built the houses on higher foundations they’d be OK," I said. "But the builder was too mean."

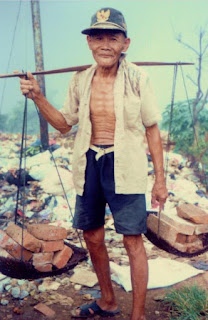

Not much further on we came to a man-made mountain range constructed of every kind of garbage. It was dark grey and smoking like a huge World War One battlefield after the guns had stopped; after all the sweet smelling flowers, all the cute furry bunny rabbits, and all the fluttery little song birds had been smashed, splintered and pulverised by machines and then buried in gangrenous filth . Now, little children, with wicker baskets on their backs, were scavenging for soggy paper and plastic and perhaps finding the arms or legs from a settee or from something else. Dangerous looking machines moved among the infants. Being probably as big as any dump in the Philippines or Egypt, it would make a marvellous tourist attraction and perhaps the shanty dwellers living on the edge of the tip could offer bed and breakfast and unusual souvenirs.

We motored on past flat fields and over wide canals to a more heavily populated area. It had stopped raining.

"Is it much further to your relations’ house?" I asked. "You said it was near Teluk Gong." I was beginning to feel hungry and irritable.

"We’re almost there," said Wardi

We parked under some trees and set off on foot along a muddy path sided by high brick walls. This opened out onto a flat red-brown plain which stretched into the distance. It made me think of the outskirts of Marrakech on a cloudy day. I could see no trees or grass but lots of home made shanty houses built with brick, corrugated iron and even cardboard.

Improved kampungs have concrete paths and drainage ditches but such luxuries were absent here. Strange coloured human waste lay in puddles. Great chunks of red earth clung to my shoes.

"Here we are," said Wati.

We had arrived outside a small brick house and were greeted by various of Min’s cousins, uncles and aunts. The smaller children had thin limbs and slightly bulging tummies. We crammed into the front room where there was simply not enough space for us all to be comfortable. Small cakes and glasses of water were offered although I was careful to avoid actually consuming anything. Goodness knows what was in the water.

"Have another cake," said Wati.

"I’m fine thanks. Haven’t quite finished the first one yet," I said. I couldn’t hide the cake in my pocket as there was always someone staring at me.

The conversation was in Sundanese which was Greek to me. I grew tired of staring at their few possessions: a calendar showing a mosque, a metal bed, several school exercise books, a broken mirror and a battered wardrobe.

"Can I use the toilet?" I asked.

An uncle led me outside and pointed to a muddy ditch a few feet from the well. A mobile stall selling noodles had arrived in the street and a crowd had gathered. Oh dear. I wandered down the road but everywhere there were people: playing chess, flying kites, sweeping the path, hanging out washing, tending their fighting cocks, having a good gossip, or tinkering with motorbikes. I reached the canal where other people had gathered to wash their hands. Ah well, when in Cengkareng, do as the locals do.

The following day, in Kem Chiks little supermarket in South Jakarta, a place where foreigners can buy everything from imported avocados to imported zit cream, I bumped into an amiable expat acquaintance called Tom. In appearance, Tom looked a little like Groucho Marks. We decided to have coffees and Danish pastries in the upstairs cafe.

I told Tom about the skinny children I had seen in Cengkareng.

"Probably got worms," said Tom, with a trace of a Manchester accent. "Almost everyone’s got them."

"Not very healthy," I said, while noting bachelor Tom’s pallid complexion and bald patch.

"You know places like Malaysia and the Philippines spend about five times as much on health as Indonesia does," said Tom, who had trained as an accountant and had a head for figures.

"But I have to say the people in Cengkareng looked a happy bunch."

"It’s the communal thing," said Tom. "They’ve all got lots of friends. Not like in Britain."

"You still like the life here?" I asked.

"In my next reincarnation I wouldn’t mind being in Bali."

"You believe in reincarnation?"

"Well it’s one of the more logical explanations of things," said Tom. "I want to find out a bit more about Islam."

"Your Moslem girl friend? What age is she?" I had first met Tom while having a drink with Fergus at the Hyatt Aryaduta Hotel. It was there that Tom had told his friend Fergus about this girl moving into his house.

"She’s now sixteen," said Tom very calmly. "She was a little younger when I first met her, but I didn’t sleep with her until her sixteenth birthday. She wants to marry me."

I was startled, but tried not to show it; I wanted to appear as an experienced man of the world.

"You’re forty something?" I asked. I looked again at Tom’s thinning hair.

"Yup. I don’t want marriage. It’s her idea. I thought about marriage but I don’t want all the complications, like becoming a Moslem and being married to her entire extended family."

"You look worried," I said.

"I am. She’s very determined about the marriage thing."

"What are her parents like?"

"Nice enough, but not exactly sophisticated. It’s her friends I don’t like. She used to work in a bar and I don’t like some of the people she worked with. Really tough people."

28. ENGAGED

Some days after our meeting in the supermarket at Kem Chiks, Tom invited me for an evening drink at the Houghmagandy Hotel in South Jakarta’s Blok M. The Houghmagandy, a modest concrete tower on a street full of noisy buses and traffic fumes, is frequented by the sort of businessmen who cannot afford Five Star establishments, or who do not mind being hassled by the multitude of young women in the extremely dark and crowded bar on the top floor.

"Kent, I need your advice," Tom whispered, as we sat down with our beers in the almost empty lower-floor restaurant. Tom was looking peaky, slightly unshaven and a trifle dishevelled in old T-shirt and baggy grey trousers.

"The sixteen-year-old girlfriend?" I said.

"Her name’s Kuntil," said Tom, his voice sounding a little more confident. "I’m in trouble."

"What’s happened?"

"She came to the office and asked to see the boss."

"You’re still working in Sudirman?"

"Yes. Anyway, the receptionist told her the boss was away. Our receptionist’s sweet. Kuntil said she’d be back and she was going to write a letter to the press. Can you imagine the story?"

" I can," I said. "‘British expatriate, aged 43, working for the well known British firm of whatever, has broken his promise to marry Moslem girl, aged 16.’ How would your boss react?"

"He’s a man of the world," said Tom, "but the firm doesn’t want that kind of publicity. My contract would probably be ended."

"Do you think she would write to the newspapers? I mean, what would she gain if you had to leave the country?"

"Revenge."

"Seems to be important in this part of the world."

"I’ve gone off her," said Tom, now speaking quite loudly. "She wants eighty million rupiahs because she says I’ve broken my promise to marry. I think it’s her friends from the karaoke bar who’ve put her up to it."

"Criminals, I reckon. Tell me, what age was she when you first met?"

"Fifteen. But, I didn’t get involved deeply until she was sixteen. I was careful."

"Have you negotiated with her?"

"I went to see her parents. They’re quite nice really. I explained that I had promised to marry her, but that I’d changed my mind."

"How did they take it?"

"They were polite and friendly. But Kuntil is sticking to her demands."

"She’s no doubt disappointed she’s not going to escape from the kampung into a life of luxury with maids and drivers and your retirement home in Madeira. My advice is to talk to her, kindly. Give her a way out that won’t involve loss of face."

"It’s not that I’m hard up, but I’ve saved my money so I can retire early."

"Is your money in shares?"

"It’s all in an Indonesian bank that’s giving a huge rate of interest."

"Is that safe?"

"The manager told me he’d let me know if there were ever any problems."

"If his bank was in difficulty, is it likely he’d let you know?"

"He’s a very decent guy," said Tom, stretching himself and beginning to look less tense. "What are you doing at the weekend? Bogor again?"

"Yes, Bogor again," I said.

In Bogor my first visit was to Ciah and her son Agosto, in their wooden shack under the dark, damp trees. Agosto was home from hospital, recovered from his typhoid, but looking pale, thin and unsmiling. I gave Ciah a small sum of money to buy food.

"Sorry it’s not much," I said, "but there have been a lot of people getting ill recently."

To be honest, I could have given a lot more, but for some reason I was feeling grumpy. Maybe it was the after effect of the beers with Tom.

In the children’s ward at Bogor’s mental hospital in Babakan I visited the mentally backward youngsters, John, Daud, Erwin and Saepul. John was naked, tied up, and sitting in a pool of diarrhoea. Erwin was locked behind bars in his usual small cell.

"John’s lost some weight," I said to the nurse named Diana, a well-nourished woman who looked happy in her work. "Has he seen the doctor?"

"Yes," she said, grinning in a way that suggested possible insensitivity or malice.

"What’s wrong with him?"

"He’s greedy. He ate too much and got sick."

"Is he getting any medicine?"

"He’s OK."

"He looks ill; malnourished."

"No. He’s fine." What was it about Diana’s smile?

I took Daud and Saepul for a short walk in the hospital grounds, and then washed my hands.

I dropped in on Asep and little Andi in Bogor Baru. Asep was still getting his TB medicine and had put on some weight around his face and chest. Andi was running around with his friends, but his stomach still had that swollen appearance of the malnourished.

Next stop was at the house of Dian, the sister of Melati and Tikus. Dian showed me her TB pills and smiled from a face that had put on more flesh and become prettier.

"Kent, I need your advice," Tom whispered, as we sat down with our beers in the almost empty lower-floor restaurant. Tom was looking peaky, slightly unshaven and a trifle dishevelled in old T-shirt and baggy grey trousers.

"The sixteen-year-old girlfriend?" I said.

"Her name’s Kuntil," said Tom, his voice sounding a little more confident. "I’m in trouble."

"What’s happened?"

"She came to the office and asked to see the boss."

"You’re still working in Sudirman?"

"Yes. Anyway, the receptionist told her the boss was away. Our receptionist’s sweet. Kuntil said she’d be back and she was going to write a letter to the press. Can you imagine the story?"

" I can," I said. "‘British expatriate, aged 43, working for the well known British firm of whatever, has broken his promise to marry Moslem girl, aged 16.’ How would your boss react?"

"He’s a man of the world," said Tom, "but the firm doesn’t want that kind of publicity. My contract would probably be ended."

"Do you think she would write to the newspapers? I mean, what would she gain if you had to leave the country?"

"Revenge."

"Seems to be important in this part of the world."

"I’ve gone off her," said Tom, now speaking quite loudly. "She wants eighty million rupiahs because she says I’ve broken my promise to marry. I think it’s her friends from the karaoke bar who’ve put her up to it."

"Criminals, I reckon. Tell me, what age was she when you first met?"

"Fifteen. But, I didn’t get involved deeply until she was sixteen. I was careful."

"Have you negotiated with her?"

"I went to see her parents. They’re quite nice really. I explained that I had promised to marry her, but that I’d changed my mind."

"How did they take it?"

"They were polite and friendly. But Kuntil is sticking to her demands."

"She’s no doubt disappointed she’s not going to escape from the kampung into a life of luxury with maids and drivers and your retirement home in Madeira. My advice is to talk to her, kindly. Give her a way out that won’t involve loss of face."

"It’s not that I’m hard up, but I’ve saved my money so I can retire early."

"Is your money in shares?"

"It’s all in an Indonesian bank that’s giving a huge rate of interest."

"Is that safe?"

"The manager told me he’d let me know if there were ever any problems."

"If his bank was in difficulty, is it likely he’d let you know?"

"He’s a very decent guy," said Tom, stretching himself and beginning to look less tense. "What are you doing at the weekend? Bogor again?"

"Yes, Bogor again," I said.

In Bogor my first visit was to Ciah and her son Agosto, in their wooden shack under the dark, damp trees. Agosto was home from hospital, recovered from his typhoid, but looking pale, thin and unsmiling. I gave Ciah a small sum of money to buy food.

"Sorry it’s not much," I said, "but there have been a lot of people getting ill recently."

To be honest, I could have given a lot more, but for some reason I was feeling grumpy. Maybe it was the after effect of the beers with Tom.

In the children’s ward at Bogor’s mental hospital in Babakan I visited the mentally backward youngsters, John, Daud, Erwin and Saepul. John was naked, tied up, and sitting in a pool of diarrhoea. Erwin was locked behind bars in his usual small cell.

"John’s lost some weight," I said to the nurse named Diana, a well-nourished woman who looked happy in her work. "Has he seen the doctor?"

"Yes," she said, grinning in a way that suggested possible insensitivity or malice.

"What’s wrong with him?"

"He’s greedy. He ate too much and got sick."

"Is he getting any medicine?"

"He’s OK."

"He looks ill; malnourished."

"No. He’s fine." What was it about Diana’s smile?

I took Daud and Saepul for a short walk in the hospital grounds, and then washed my hands.

I dropped in on Asep and little Andi in Bogor Baru. Asep was still getting his TB medicine and had put on some weight around his face and chest. Andi was running around with his friends, but his stomach still had that swollen appearance of the malnourished.

Next stop was at the house of Dian, the sister of Melati and Tikus. Dian showed me her TB pills and smiled from a face that had put on more flesh and become prettier.

I wandered alongside one of Bogor’s red-brown river gorges. To my right was the volcano, Mount Salak. To my left little kampung houses were clinging to a series of steep terraces; colour was provided by sky blue doors, red-brown cockerels in cages and sheeny pink bougainvillea in tiny gardens; a food cart vendor was seeking attention by knocking on a hollow bamboo stick; a young girl in a too short skirt was slowly climbing some wide stone steps; drifting down the river was a raft covered in semi-naked children.

"Hey mister. Come in." It was the voice of young Dede, fan of English football, and brother of the fragrant and beautiful Rama. Dede, dressed in school uniform, was sitting on the wall outside his house.

"OK," I said, pleased to have some company.

Once seated on the concrete floor of his front room, Dede took a cigarette from behind his ear and lit it with a match he had rubbed against the wall. He began blowing smoke rings. There was a slight movement of the curtain leading to the bedroom, suggesting someone was on the other side.

Seated on the lumpy settee, I looked at a framed photo positioned on top of the TV. In the photo, Rama was holding hands with a tall, ungainly young man with a big forehead, hollow cheeks and a facial expression suited to a spivvish barrow-boy.

"My sister," said Dede. "She’s got engaged."

"To the man in the photo?" I asked with a slight croak in my voice. It seemed incredulous that Rama should want to marry someone so less attractive than herself.

"Correct."

"Does he live near here?"

"Round the corner," said Dede. "His mum is friends with my mum. They’re distant relations."

Before I had time to think too deeply about Rama’s fate, a small boy, dressed in a sarong, appeared at the open door and stared in. He was accompanied by a grey old lady I took to be his granny.

"This is Hadi," said Dede, pointing in the direction of the elfin kid. "He’s just been circumcised."

"Brave chap," I said.

"Hadi," said Dede, addressing the lad, "show mister where you’ve had the operation."

The boy grinned and shook his head.

"Want to see my barbet?" asked Dede, cocking his head to one side.

"Your what?"

"Barbet," said Dede, dark eyes widening.

"Barbet?"

"Do you like barbets?" asked Dede. "I’ll show you it."

He went into the small front garden and returned with a tiny quivering object.

"Do you like birds?" he said, as he opened his hands to reveal the feathery fledgling.

"Yes, but not in cages," I said, feeling sorry for the creature. "There are hardly any birds in the trees around here. They’re all in cages."

He sat on the floor and let the bird walk over his head.

"Be careful. It may not be clean," I advised. "You don’t want to catch some disease."

"Oman’s ill," said Dede.

"Who’s Oman?" I asked.

"A little kid down the road," said Hadi. "He’s got typhoid."

"Has he been to the doctor?" I asked, suspecting that I already knew the answer.

"The dukun’s been to see him," said Dede. "And, his aunt’s ill as well."

"What’s wrong with her?" I said.

"She’s all swollen up," said Hadi.

"Has she seen a doctor?" I asked.

"No," said Dede. "The dukun treated her as well."

"We’d better go and see them," I said, with some reluctance. I felt I had already had enough hassle for the day.

Dede led me to a white walled kampung house inside which were lots of small rooms, all dingy, dark and untidy. There were grubby paw marks on walls; and in one room, piles of threadbare clothes covered a torn settee. We entered a room smelling of rotting meat. Lying on a mattress on the floor was a middle aged woman, named Nurul, whose legs and arms looked swollen to twice their normal size.

"Have you seen a doctor?" I asked.

"She’s been getting treatment from the dukun," said a young man standing by the door. "The dukun did something which made her bleed. But she’s no better."

"She looks fevered. How long has she been like this?" I said.

"Maybe ten days," said the young man.

"Do you want to go to the hospital, if I pay?" I asked Nurul.

"Yes," she whispered.

"Where’s Oman?" I said.

I was taken into a room off a back courtyard. Ten year old Oman, who was lying on a settee, looked like a skeletal creature from a Japanese internment camp.

"Has he seen a doctor?" I asked.

"We took him to the government clinic," said a plump woman with a kindly face and broken sandals. "They gave him some pills for typhoid, but they didn’t work."

"You got pills for how many days?" I inquired.

"Three days," said the woman.

"Did you go back to the clinic when the pills were finished?"

"No," she said, smiling.

"How long ago was that?"

"About a week ago." She looked unsure.

"Do you want him to go to the hospital?"

"He’s been to the dukun," she said, avoiding looking at me.

"But he’s not better," I pointed out.

"Give us the money for the hospital and we’ll go later," said a man who appeared at the door of the room. Unshaven, and dressed in a snazzy shirt, he looked like a down-market used-car-salesman.

"Who are you?" I asked.

"Joko, Oman’s father," said the man.

"Why can’t we go to the hospital now?" I asked.

"I’ve got to go off to the market to work," said Joko. "My wife’s got to look after the other children."

"We’ve got to go now," I insisted. "Look. Nurul’s being taken now." Six young men had appeared carrying the sick woman on a stretcher.

Joko put Oman on his shoulders and we set off towards my van.

At the Menteng Hospital the doctor looked worried after examining Nurul.

"She suffers from diabetes," said the doctor, "but she’s also got septicaemia, blood poisoning. She should have been here when she first got ill." Nurul was wheeled away to the third class women’s ward.

Oman was fitted to a drip and the nurse handed me a prescription for pills to last three days.

"Typhoid?" I asked.

"Yes," said the nurse, a pretty girl in a tight white uniform.

"Can we not get medicine to last more than three days?"

"No. It’s always three days," she said.

"But I live in Jakarta."

"Maybe Oman’s father can buy the next lot of medicine."

I turned to Joko. "If I give you medicine money to last ten days, will you make sure it’s used only to buy your son’s medicines?"

"OK," said Joko, avoiding my gaze.

29. RAMADAN

Three days after I had taken ten-year-old Oman to the Menteng Hospital in Bogor there was an early evening phone call from a nurse at the hospital. She said that Oman was making good progress, but, the medicine had run out and I must come to the hospital immediately to buy some more. I explained to the nurse that I had already given Joko, the child’s father, more than enough money to pay for a further ten days typhoid medicine. The nurse said that the family claimed they had no money left to pay for the prescription.

Having had a quick supper, I got my driver to hurry me to the hospital in Bogor. Oman’s cheerful, chunky, poorly-dressed mother, accompanied by a bubbly-nosed toddler, was waiting at the boy’s bedside. Oman looked a little less grey and cadaverous.

"A few days ago I gave Joko the cash for the next lot of medicine," I said to the mother, trying to sound as stern as possible. "What’s happened to it?"

"I don’t know," she said, looking totally unflustered. "He hasn’t given me any."

"I gave him plenty," I growled.

"It would be better not to give him money," she said, in a matter-of-fact sort of way. It seemed that the lady did not necessarily have a high regard for her husband’s honesty.

I bought the required pills and handed them over to the nurse. After a quick visit to the women’s ward to see Nurul, whose septicaemia seemed to have made her flesh worryingly dark, I set off to Joko’s house. Joko, wearing a glittery shirt, was seated by his front door; he was playing chess with a shifty-looking friend.

"What happened to the money I gave you for Oman’s medicine?" I asked, with a combination of anger and nervousness.

"I haven’t got it," he said, keeping his eyes on the chess pieces.

"You know I gave you plenty."

"I had to pay for transport to the hospital," said Joko, giving me a quick glance with his untrustworthy eyes.

"I gave you enough for food, transport and loads of pills. The bus only costs a few cents. What happened to the cash?"

"It’s finished," he said, as he made his next chess move.

"It’s your son that’s sick," I said. At least I assumed it was his son. "What would have happened if I hadn’t come to the hospital this evening?"

There was no reply. He looked unmoved.

I glanced inside Joko’s house. Was that a new suite of furniture and were these new toys lying by the door?

I was going to have to get my poor driver to visit the hospital during the following days in order to buy the next lots of medicine for Oman.

A week and a half later I returned to the Menteng Hospital. A very young and pretty nurse told me that Oman had recovered from his typhoid and gone back home. But, Nurul, Oman’s aunt, had died as a result of her blood poisoning. I called in at Oman’s house to commiserate on the death of Nurul, and to remind the family that Oman would need to return to the hospital later in the week for a check up. Oman was painfully thin, but he was a normal colour and he was playing with a large plastic toy car.

When Oman’s father, Joko, emerged from a back courtyard, I prepared to launch into a verbal attack. But Joko presented me with a parcel, inside which was a black and gold batik shirt.

"Thank you, Mr Kent," said Joko, grinning.

We shook hands and I wondered if I had slightly misjudged the man.

"Lots of Indonesians getting ill recently," I said to Tom, as we sat down to a beer in the bar at the middle-range Marco Polo Hotel, "It’s amazing how many people get typhoid and TB."

"Too true," said Tom, who was looking vaguely in the direction of a long-legged young Indonesian girl seated on a black bar stool.

"I came across a kampung kid who nearly died of typhoid."

"They die of tetanus every week in the kampungs," said Tom, looking serious.

"And how are things with you ?" I asked, knowing that Tom had invited me out to talk about his girl problems rather than typhoid.

"Better. I’ve done a deal with Kuntil."

"What happened?"

"We had a long talk. I stayed quite calm about it all. I said she could have fifty million rupiahs and that was my final offer. She accepted and I got her to sign a piece of paper in which she promises to make no more trouble. We shook hands on that."

"That’s a lot of money."

"I wanted the thing settled. The lesson for me is that I’m not going to try any more long-lasting relationships with the locals."

"Long-lasting?"

"If I meet a girl in a bar, it’s for that night only."

"You don’t want to settle down?"

"The trouble with Kuntil was that, although she was nice to begin with, after a few weeks of living at my place there were problems. Things started to disappear. Money went missing. She asked for money for her relatives."

"Are you sure it was her that was taking things?"

"I found one of my watches in her handbag. Now, how could I marry a girl I couldn’t trust?"

"I see what you mean. But you did meet her in a karaoke bar."

We were into 1993 and the Moslem month of fasting, Ramadan, had come round again. I was seated with Carmen, my small, bubbly, middle-aged colleague, in the front room of my Moslem neighbour, Mr Samsu. A kindly, white haired, little polar-bear of a man, Samsu had not long retired from teaching science at a local university. His modest bungalow was full of books, many of them in English and many of them about Islam. Carmen and I liked to call in on Samsu because we could have a serious conversation with a Moslem who was traditional rather than orthodox. Traditional Moslems, the majority in Indonesia, tend to be more liberal than orthodox Moslems.

"Ramadan," said Carmen, beaming, "it’s a difficult time of year for me. My maid’s going off to East Java, to Surabaya, for the ten day Idul Fitri holiday. How am I going to survive? I’ve almost forgotten how to do housework."

"We have a maid," said Samsu, in a gentle voice, "but my wife has always got involved with the housework."

I looked at the spotless floor and at the cobwebs on the ceiling. In Indonesia, floors always seemed to have a higher priority than ceilings.

"Ramadan is supposed to remind Moslems what it feels like to be one of the poor," said Carmen, with a friendly giggle, "what it feels like to be hungry."

"Exactly," said Samsu, who was looking slightly grey, either because of the fasting or because of the room’s dull lighting. "As it says in Islam, unless you want for your neighbour what you want for yourself, you are not a faithful believer."

"How many Moslems and Christians remember that?" said Carmen, with a guffaw. "Think of all the religious leaders who have wanted to stone people to death. Would they have wanted themselves to be stoned to death?"

Samsu chose to ignore the remark. "Here’s another quote from Islam," said Samsu, gravely. "‘The man who goes to bed with his stomach full, while his neighbour is starving, is not a believer.’ Now think how many hungry people live around here, and think how many full-bellied Moslems and Christians there are in the rich neighbourhood of Pondok Indah."

"I heard of someone in the Ministry of Religious Affairs," said Carmen, "who allegedly owns four large houses and three large cars. Shouldn’t he be giving extra money to his maids?"

"What I’m worried about," I said, "is that my maid wants extra money, not because she’s hungry, but because she wants to buy posh clothes for the Idul Fitri holiday, and buy expensive travel tickets. I gather that ticket scalpers see this time of year as a chance to put up the price of bus tickets by three hundred per cent."

"It’s like Christmas," said Samsu, eyes twinkling. "Some people forget what Christmas is supposed to be about."

"More stories in the papers about Moslems and Christians in Bosnia," said Carmen, stirring things up. "Two years ago it was Iraq and the Gulf War."

"Always lots of problems," said Samsu.

"I saw some graffiti on a wall," continued Carmen. "It was graffiti supporting Saddam Hussein."

I decided to sit back and just listen to the two of them. They seemed to be enjoying themselves.

"Ignorant youth," said Samsu, grinning and shaking his head. "I don’t mean you. I mean the graffiti artist. Moslems are meant to support love, not war. ‘God does not love aggressors.’ That’s Chapter two, verse one hundred and ninety, from the Koran."

"So, is Saddam an aggressor?" asked Carmen.

"I was thinking the graffiti was perhaps aggressive," said Samsu, with a diplomat’s smile. "As for Saddam, let us consider some History. When the Turkish Ottoman Empire collapsed after World War I, the British created Iraq out of the Ottoman provinces of Mosul, Baghdad, and Basrah. Kuwait was part of Basrah, but the British decided to keep Kuwait for themselves. Some people might say that Saddam was taking back land that should rightly be part of Iraq."

"Why is Saddam popular with some Indonesians?" continued Carmen.

"Because another neighbour’s land has been invaded, and that invasion has been supported by the United States," said Samsu, looking hard at Carmen to see her reaction.

"Another invasion?" asked Carmen.

"Israel has taken lots of Arab land," said Samsu, without any trace of aggression, "and Saddam is seen as someone who can stand up to Israel. Don’t forget that the Americans created the Saddam problem. Saddam was almost certainly put into power by the CIA."

"You think it’s like the mid-1960s," said Carmen.

"The mid-1960s," said Samsu. "That was when the CIA put the military into power in Greece."

"I was thinking of a different military," said Carmen.

"Think of 1963," said Samsu. "The Iraqi Prime Minister, Qasim, was not doing what the Americans wanted. Saddam was one of the people who helped to topple Qasim in 1963. Saddam was useful to the Americans, just as the Ayatollahs in Iran were useful to the Americans. Saddam killed off left-wingers. The Ayatollahs killed off left-wingers. America probably helped to topple the Shah of Iran when he became too powerful and independent. Of course the Americas did not want either the Ayatollahs or Saddam to become too powerful, so they encouraged Iraq and Iran to go to war in 1980. The CIA gave help to both sides in the Iran-Iraq war. In 1990, the Americans achieved their aim of getting military bases in Saudi Arabia, thanks to Saddam’s adventure in Kuwait."

"The Americans are responsible for a lot of the world’s problems," said Carmen. "For a supposedly Christian-led nation, they can be very aggressive."

Having had a quick supper, I got my driver to hurry me to the hospital in Bogor. Oman’s cheerful, chunky, poorly-dressed mother, accompanied by a bubbly-nosed toddler, was waiting at the boy’s bedside. Oman looked a little less grey and cadaverous.

"A few days ago I gave Joko the cash for the next lot of medicine," I said to the mother, trying to sound as stern as possible. "What’s happened to it?"

"I don’t know," she said, looking totally unflustered. "He hasn’t given me any."

"I gave him plenty," I growled.

"It would be better not to give him money," she said, in a matter-of-fact sort of way. It seemed that the lady did not necessarily have a high regard for her husband’s honesty.

I bought the required pills and handed them over to the nurse. After a quick visit to the women’s ward to see Nurul, whose septicaemia seemed to have made her flesh worryingly dark, I set off to Joko’s house. Joko, wearing a glittery shirt, was seated by his front door; he was playing chess with a shifty-looking friend.

"What happened to the money I gave you for Oman’s medicine?" I asked, with a combination of anger and nervousness.

"I haven’t got it," he said, keeping his eyes on the chess pieces.

"You know I gave you plenty."

"I had to pay for transport to the hospital," said Joko, giving me a quick glance with his untrustworthy eyes.

"I gave you enough for food, transport and loads of pills. The bus only costs a few cents. What happened to the cash?"

"It’s finished," he said, as he made his next chess move.

"It’s your son that’s sick," I said. At least I assumed it was his son. "What would have happened if I hadn’t come to the hospital this evening?"

There was no reply. He looked unmoved.

I glanced inside Joko’s house. Was that a new suite of furniture and were these new toys lying by the door?

I was going to have to get my poor driver to visit the hospital during the following days in order to buy the next lots of medicine for Oman.

A week and a half later I returned to the Menteng Hospital. A very young and pretty nurse told me that Oman had recovered from his typhoid and gone back home. But, Nurul, Oman’s aunt, had died as a result of her blood poisoning. I called in at Oman’s house to commiserate on the death of Nurul, and to remind the family that Oman would need to return to the hospital later in the week for a check up. Oman was painfully thin, but he was a normal colour and he was playing with a large plastic toy car.

When Oman’s father, Joko, emerged from a back courtyard, I prepared to launch into a verbal attack. But Joko presented me with a parcel, inside which was a black and gold batik shirt.

"Thank you, Mr Kent," said Joko, grinning.

We shook hands and I wondered if I had slightly misjudged the man.

"Lots of Indonesians getting ill recently," I said to Tom, as we sat down to a beer in the bar at the middle-range Marco Polo Hotel, "It’s amazing how many people get typhoid and TB."

"Too true," said Tom, who was looking vaguely in the direction of a long-legged young Indonesian girl seated on a black bar stool.

"I came across a kampung kid who nearly died of typhoid."

"They die of tetanus every week in the kampungs," said Tom, looking serious.

"And how are things with you ?" I asked, knowing that Tom had invited me out to talk about his girl problems rather than typhoid.

"Better. I’ve done a deal with Kuntil."

"What happened?"

"We had a long talk. I stayed quite calm about it all. I said she could have fifty million rupiahs and that was my final offer. She accepted and I got her to sign a piece of paper in which she promises to make no more trouble. We shook hands on that."

"That’s a lot of money."

"I wanted the thing settled. The lesson for me is that I’m not going to try any more long-lasting relationships with the locals."

"Long-lasting?"

"If I meet a girl in a bar, it’s for that night only."

"You don’t want to settle down?"

"The trouble with Kuntil was that, although she was nice to begin with, after a few weeks of living at my place there were problems. Things started to disappear. Money went missing. She asked for money for her relatives."

"Are you sure it was her that was taking things?"

"I found one of my watches in her handbag. Now, how could I marry a girl I couldn’t trust?"

"I see what you mean. But you did meet her in a karaoke bar."

We were into 1993 and the Moslem month of fasting, Ramadan, had come round again. I was seated with Carmen, my small, bubbly, middle-aged colleague, in the front room of my Moslem neighbour, Mr Samsu. A kindly, white haired, little polar-bear of a man, Samsu had not long retired from teaching science at a local university. His modest bungalow was full of books, many of them in English and many of them about Islam. Carmen and I liked to call in on Samsu because we could have a serious conversation with a Moslem who was traditional rather than orthodox. Traditional Moslems, the majority in Indonesia, tend to be more liberal than orthodox Moslems.

"Ramadan," said Carmen, beaming, "it’s a difficult time of year for me. My maid’s going off to East Java, to Surabaya, for the ten day Idul Fitri holiday. How am I going to survive? I’ve almost forgotten how to do housework."

"We have a maid," said Samsu, in a gentle voice, "but my wife has always got involved with the housework."

I looked at the spotless floor and at the cobwebs on the ceiling. In Indonesia, floors always seemed to have a higher priority than ceilings.

"Ramadan is supposed to remind Moslems what it feels like to be one of the poor," said Carmen, with a friendly giggle, "what it feels like to be hungry."

"Exactly," said Samsu, who was looking slightly grey, either because of the fasting or because of the room’s dull lighting. "As it says in Islam, unless you want for your neighbour what you want for yourself, you are not a faithful believer."

"How many Moslems and Christians remember that?" said Carmen, with a guffaw. "Think of all the religious leaders who have wanted to stone people to death. Would they have wanted themselves to be stoned to death?"

Samsu chose to ignore the remark. "Here’s another quote from Islam," said Samsu, gravely. "‘The man who goes to bed with his stomach full, while his neighbour is starving, is not a believer.’ Now think how many hungry people live around here, and think how many full-bellied Moslems and Christians there are in the rich neighbourhood of Pondok Indah."

"I heard of someone in the Ministry of Religious Affairs," said Carmen, "who allegedly owns four large houses and three large cars. Shouldn’t he be giving extra money to his maids?"