20. BABY

Early next morning I collected Min from Wisma Utara and we set off for Teluk Gong where we were due to meet Min’s family. At the start of the journey, Min seemed a bit solemn but fortunately no worse than that. My new driver impressed me not only with his careful driving but also with his calm and sympathetic tone when addressing Min.

As we moved through the traffic I thought of what I had been writing in my diary the night before. How objective was it? I honestly couldn’t remember with one hundred per cent accuracy how each member of Min’s family had reacted to him on his return to his family home. I was not confident that I had recorded the conversations with total fairness and without error.

I suspected that my diary, like many works of non-fiction, was full of selectivity, prejudice and opinion, as opposed to fact. Probably I selected the bits that put me in a good light; probably I failed to notice lots of significant things that happened.

I suspect that if Min’s brother, Wardi, had written a diary of these events it would have contained some major differences of interpretation.

Did the family want Min to continue for a bit longer at his school? Were they interested in moving to a house near Wisma Utara? I did not know. They had a Sundanese-Javanese way of being reluctant to voice their opinions, particularly to someone richer than themselves. Their ideas and attitudes were influenced not only by universal human nature but also by their own local world which I did not fully understand.

Min perked up as we approached his home in the slums near the airport; he stood up in his seat and called out exultantly, "Min, Min."

We parked beside a vegetable stall, climbed out of the vehicle, and were met by Min’s big brother, Wardi, Min’s mother, Wati, Min’s two little brothers, Aldi, aged about eleven, and Itin, aged about five, and little sister Imah, aged about four. They had all put on their best clothes and were looking a bit ill at ease. It occurred to me that maybe they felt intimidated by people like me who arrived in big cars.

"How about a trip to Ragunan zoo in South Jakarta?" I asked, after we had exchanged greetings.

"OK," said Wardi, with a touch of a smile. Wati nodded in approval.

"Have you been there before?" I asked.

"No, Mr Kent. We have no money," explained Wardi.

We crowded into my Mitsubishi van and set off down the narrow potholed street. Happy, almost jubilant, expressions began to appear on the faces of Wati, Wardi and Aldi as we were chauffeur-driven past bemused neighbours, barefoot children and skinny goats. The morning sun was shining brightly and I was happy to be having another adventure.

As we drove towards the zoo in Pasar Mingu, I had lots of questions for Wardi and Wati. "Where does your family come from originally?" I inquired. "Have you always lived in Jakarta?"

"We used to live near Lamaya," said Wardi. "It’s a four hour journey from Jakarta. Lots of rice fields in Lamaya. We had to move because there’s no work there. Too many people."

"Would you like to go back to Lamaya one day?" I asked Wardi.

"Yes, but we have to live in Jakarta because that’s where the jobs are."

"Do you have other relatives here in Jakarta?" I asked.

"Lots, Mr Kent," said Wati, smiling. "In Teluk Gong and Cengkareng."

After a journey of about ten miles we reached the enormous park that contains Jakarta’s zoo, an institution that tries to keep at least some of its animals in quarters that resemble natural habitats. Having bought our inexpensive tickets at a dark little booth, we began our tour. We seemed to be almost the only visitors. There was something eerie about the atmosphere that morning. We passed under immense dark trees that completely blocked out sun and sky; we heard the constant screams of monkeys; there was a smell of rotting meat.

I noted that Min’s mum gave all her attention to four-year-old Imah, whom she carried in her arms; Wardi took the hand of five-year-old Itin; small, skinny, eleven-year-old Aldi walked on his own; Min held onto me. I was touched by Min’s trust, but would have preferred to see him take the hand of a member of his own family. In Indonesia I had noticed that many mothers devoted their energies almost exclusively to the baby of the family; older children either fended for themselves or were looked after by such people as uncles, big sisters and grannies. Who was going to be Min’s keeper?

We approached the compound containing the Java tiger. Min was terrified and tried to pull me away in the direction of the zoo’s exit.

We moved on swiftly to the monkeys. Min refused to look and again pulled at my arm. I couldn’t take him near the crocodiles or the Komodo dragons, but eleven year-old Aldi was enjoying himself.

I was fascinated by the weirdness of everything around me. What might make a being want to develop into something as big and ugly and savage as a Komodo dragon? Do beings such as trees and butterflies make choices? I had been told that a considerable number of Indonesians believe that even trees have spirits. Could Min perhaps see more than the rest of us? Was that why he was afraid?

After an hour-long visit to Ragunan zoo, and a quick snack of noodles, we battled back through Jakarta’s traffic to the family’s house in the Teluk Gong area, near the sea.

This time I wanted to have a closer look at the kampung, the local area, in which Min had been brought up. I wanted to get a clearer idea of how safe it was, or how dangerous.

"Shall we take a walk with Min?" I said to Wardi, as we stood at the front door of the wooden shack which was home to Min’s family.

"OK," came the reply. "You’ll need to watch your feet."

Wardi, Min and I walked along wooden gangways, taking us over fetid water, and then along muddy paths, taking us through narrow alleys sided by wooden shacks. The sky was a heavenly blue and the sun’s strong light created streaks of golden light and black shadow.

"Who’s this?" I asked Wardi about a little boy with deformed legs. The boy, who looked about ten years of age, was hauling himself along the ground towards his wooden house. One leg had a zigzag shape and looked beyond repair.

"Don’t know," he replied. But he asked the woman who came to the door.

"My son’s called Saepul," said the woman. Like her son, she had a facial expression that spoke of sadness, resignation and kindness. Every inch of her face and arms was covered in big fleshy lumps.

"Have you and your son been to a doctor?" I asked the woman.

"We’ve been to the hospital," she said. "Saepul was born this way. The doctors say an operation might not help him. They’re not sure."

"And you?" I asked.

"They can’t do anything for me. But it won’t get any worse."

"I hope to see you again sometime," I said. I presumed that if the doctor had recommended treatment, they would have had no money to pay for it.

As we moved through the traffic I thought of what I had been writing in my diary the night before. How objective was it? I honestly couldn’t remember with one hundred per cent accuracy how each member of Min’s family had reacted to him on his return to his family home. I was not confident that I had recorded the conversations with total fairness and without error.

I suspected that my diary, like many works of non-fiction, was full of selectivity, prejudice and opinion, as opposed to fact. Probably I selected the bits that put me in a good light; probably I failed to notice lots of significant things that happened.

I suspect that if Min’s brother, Wardi, had written a diary of these events it would have contained some major differences of interpretation.

Did the family want Min to continue for a bit longer at his school? Were they interested in moving to a house near Wisma Utara? I did not know. They had a Sundanese-Javanese way of being reluctant to voice their opinions, particularly to someone richer than themselves. Their ideas and attitudes were influenced not only by universal human nature but also by their own local world which I did not fully understand.

Min perked up as we approached his home in the slums near the airport; he stood up in his seat and called out exultantly, "Min, Min."

We parked beside a vegetable stall, climbed out of the vehicle, and were met by Min’s big brother, Wardi, Min’s mother, Wati, Min’s two little brothers, Aldi, aged about eleven, and Itin, aged about five, and little sister Imah, aged about four. They had all put on their best clothes and were looking a bit ill at ease. It occurred to me that maybe they felt intimidated by people like me who arrived in big cars.

"How about a trip to Ragunan zoo in South Jakarta?" I asked, after we had exchanged greetings.

"OK," said Wardi, with a touch of a smile. Wati nodded in approval.

"Have you been there before?" I asked.

"No, Mr Kent. We have no money," explained Wardi.

We crowded into my Mitsubishi van and set off down the narrow potholed street. Happy, almost jubilant, expressions began to appear on the faces of Wati, Wardi and Aldi as we were chauffeur-driven past bemused neighbours, barefoot children and skinny goats. The morning sun was shining brightly and I was happy to be having another adventure.

As we drove towards the zoo in Pasar Mingu, I had lots of questions for Wardi and Wati. "Where does your family come from originally?" I inquired. "Have you always lived in Jakarta?"

"We used to live near Lamaya," said Wardi. "It’s a four hour journey from Jakarta. Lots of rice fields in Lamaya. We had to move because there’s no work there. Too many people."

"Would you like to go back to Lamaya one day?" I asked Wardi.

"Yes, but we have to live in Jakarta because that’s where the jobs are."

"Do you have other relatives here in Jakarta?" I asked.

"Lots, Mr Kent," said Wati, smiling. "In Teluk Gong and Cengkareng."

I noted that Min’s mum gave all her attention to four-year-old Imah, whom she carried in her arms; Wardi took the hand of five-year-old Itin; small, skinny, eleven-year-old Aldi walked on his own; Min held onto me. I was touched by Min’s trust, but would have preferred to see him take the hand of a member of his own family. In Indonesia I had noticed that many mothers devoted their energies almost exclusively to the baby of the family; older children either fended for themselves or were looked after by such people as uncles, big sisters and grannies. Who was going to be Min’s keeper?

We approached the compound containing the Java tiger. Min was terrified and tried to pull me away in the direction of the zoo’s exit.

We moved on swiftly to the monkeys. Min refused to look and again pulled at my arm. I couldn’t take him near the crocodiles or the Komodo dragons, but eleven year-old Aldi was enjoying himself.

I was fascinated by the weirdness of everything around me. What might make a being want to develop into something as big and ugly and savage as a Komodo dragon? Do beings such as trees and butterflies make choices? I had been told that a considerable number of Indonesians believe that even trees have spirits. Could Min perhaps see more than the rest of us? Was that why he was afraid?

After an hour-long visit to Ragunan zoo, and a quick snack of noodles, we battled back through Jakarta’s traffic to the family’s house in the Teluk Gong area, near the sea.

This time I wanted to have a closer look at the kampung, the local area, in which Min had been brought up. I wanted to get a clearer idea of how safe it was, or how dangerous.

"Shall we take a walk with Min?" I said to Wardi, as we stood at the front door of the wooden shack which was home to Min’s family.

"OK," came the reply. "You’ll need to watch your feet."

Wardi, Min and I walked along wooden gangways, taking us over fetid water, and then along muddy paths, taking us through narrow alleys sided by wooden shacks. The sky was a heavenly blue and the sun’s strong light created streaks of golden light and black shadow.

"Who’s this?" I asked Wardi about a little boy with deformed legs. The boy, who looked about ten years of age, was hauling himself along the ground towards his wooden house. One leg had a zigzag shape and looked beyond repair.

"Don’t know," he replied. But he asked the woman who came to the door.

"My son’s called Saepul," said the woman. Like her son, she had a facial expression that spoke of sadness, resignation and kindness. Every inch of her face and arms was covered in big fleshy lumps.

"Have you and your son been to a doctor?" I asked the woman.

"We’ve been to the hospital," she said. "Saepul was born this way. The doctors say an operation might not help him. They’re not sure."

"And you?" I asked.

"They can’t do anything for me. But it won’t get any worse."

"I hope to see you again sometime," I said. I presumed that if the doctor had recommended treatment, they would have had no money to pay for it.

We moved on and came across a windowless wooden shack the size of a large dog kennel. It was surrounded by muddy water and was flooded inside. A barefoot boy, aged about twelve, emerged from the tiny door. The skin on his face and hands was dreadfully lined and wrinkled. I supposed that his skin problems were caused by flood water and malnutrition.

"Do you live here?" I asked the lad.

"Yes, with my mother." He looked and sounded weary but managed a shy smile.

"What’s your name?" I said.

"Joko," said the boy.

"Does your father live here?" I inquired.

"He’s dead," said Joko, eyes moistening.

I gave the boy some money, continued the walk, and eventually returned Min to Wisma Utara.

I was glad that Min was still staying at Wisma Utara. Min’s family seemed to be decent people, but I wasn’t sure which of them was going to take responsibility for guarding Min, and stopping him from getting lost. More seriously, Min’s house was in the sort of area where kids could so easily catch diseases such as typhoid or TB. The sooner I moved Min’s family to a new house the better. I would, in the meantime, continue to take Min to visit his family each afternoon, after school.

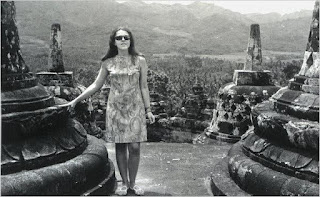

The following sunny Saturday found Min, big-brother Wardi and I on a trip to the hilly town of Bogor. We drove past the perfect lawns of the elegant white 19th century Bogor Palace, once the official residence of governor-generals of the Dutch East Indies, and on through the busy central area with its churches and mosques, its crowded markets and green minibuses. Min and Wardi seemed to be enjoying the ride.

"Is this town like Lamaya, where you used to live?" I asked Wardi.

"A little similar," he said. "Lamaya is smaller and flatter."

"Bogor has some very rich people," I commented. "What about Lamaya?"

"A few of the Chinese Indonesians there are rich."

Three kilometres south of the town, we came to a neighbourhood known as Batutulis which is named after a famous piece of stone, kept in a small museum. The Batutulis is inscribed with several words of Sanskrit which tell of the supernatural powers of a 16th century Hindu ruler of the Pajajaran kingdom. The stone is said to have mystical powers and Indonesia’s first president, Sukarno, had a home built next to it.

"Sukarno’s house," I said, pointing to my left. I wondered how much Wardi knew about Sukarno.

"Sukarno was good," said Wardi. "He is very popular in Indonesia."

"Did they teach you about him at school?"

"I only had a little schooling," he said.

We journeyed past the Sukarno residence, crossed the River Cisadane by an old and fragile looking bridge and eventually reached a railway track. It was time for a walk.

We set off along a narrow path which sided the railway track. To left and right were shanty houses and that meant peach coloured tiles, rosy bougainvillea, and the occasional red rooster. Kids in white shirts and shorts the colour of alizarin crimson danced along on their way home from school. The sky above the volcano, Mount Salak, was of a cerulean hue and above that ultramarine. The colours were as intense as any I had seen during summer holidays on the Mediterranean coast of Italy or on the Atlantic coast of Morocco. We did not see any trains.

"Hey mister," said a little school kid, "where are you from?"

"I’m from here," I replied. I felt I belonged to this world of happy smiles and immensely bright light.

"Where are you going?" said the now puzzled little person.

"Here." This was where I wanted to be. I wasn’t going anywhere in particular.

A boy came along carrying a pigeon.

"Your cat doesn’t look too well," I said.

"Pigeon," he responded, with a grin.

Wardi looked puzzled. Min yawned. Wardi might have been wondering why I had chosen to walk alongside a railway track, rather than visit the Botanic Gardens or some modern shopping centre.

"I love the Bogor countryside," I said. "I love the little houses."

"Better than the city," said Wardi.

We came to a cluster of little huts on top of a slope and I decided to take some photos. A cheery old man in a Tommy Cooper hat was seated in an armchair next to a slumbering cat and some cadmium orange cannas. Two boys were playing marbles. Above were tangles of electricity wires and a tall flowering rose of India. I got out my camera and looked through the lens. About twenty children had materialised from various alleys and they were pushing and shoving to get the best position in front of the camera. No sign of the old gentleman. He was hidden somewhere behind all these kids. There were whoops and yells and snorts. I took one photo and put my camera away.

"Hey mister," said a chunky lady with an aggressive face, "there’s a sick baby here."

"Where?" I asked.

"In the little house there," she said, pointing to a nearby one-roomed wooden hut.

It seemed like the sort of place where, in Britain, you might keep a lawnmower. While Wardi guarded Min, I stepped inside the tiny habitation. On the floor sat a young mother and a granny, and in front of them lay a baby, bluey-purple in colour, and struggling for air.

"How long has the baby been ill?" I asked.

"Five days," said the mum, who, on the surface, didn’t look particularly worried.

"The baby must go to a hospital immediately," I insisted. "Look, it’s blue because it can hardly breathe. Have you been to a doctor?"

"No," said the mum.

"We must go now," I said. "I’ll pay. OK?"

"Maybe we’ll go later," said the mum.

"When?" I asked her.

"Tomorrow."

"That’ll be too late. The baby’s nearly dead." I pointed at the blue little face.

Granny spoke for the first time. "We’ve been to the dukun. He gave us some medicine."

"The witch doctor has not got oxygen and a drip," I said, sarcastically. "The baby needs to be in a hospital. Why can’t we go now?"

"My husband’s not home yet," said the mum. "We’ll need to ask him."

"When does he get home?" I inquired.

"Late tonight," said the mum.

"Where is he now?"

"Far away," she said.

"We must go now to save the baby," I said loudly.

Granny spoke for a second time. "She doesn’t want to go."

It occurred to me that it is the conservatism of the poor that causes them so many of their problems. The elite are more adventurous.

"Sukarno’s house," I said, pointing to my left. I wondered how much Wardi knew about Sukarno.

"Sukarno was good," said Wardi. "He is very popular in Indonesia."

"Did they teach you about him at school?"

"I only had a little schooling," he said.

We journeyed past the Sukarno residence, crossed the River Cisadane by an old and fragile looking bridge and eventually reached a railway track. It was time for a walk.

We set off along a narrow path which sided the railway track. To left and right were shanty houses and that meant peach coloured tiles, rosy bougainvillea, and the occasional red rooster. Kids in white shirts and shorts the colour of alizarin crimson danced along on their way home from school. The sky above the volcano, Mount Salak, was of a cerulean hue and above that ultramarine. The colours were as intense as any I had seen during summer holidays on the Mediterranean coast of Italy or on the Atlantic coast of Morocco. We did not see any trains.

"Hey mister," said a little school kid, "where are you from?"

"I’m from here," I replied. I felt I belonged to this world of happy smiles and immensely bright light.

"Where are you going?" said the now puzzled little person.

"Here." This was where I wanted to be. I wasn’t going anywhere in particular.

A boy came along carrying a pigeon.

"Your cat doesn’t look too well," I said.

"Pigeon," he responded, with a grin.

Wardi looked puzzled. Min yawned. Wardi might have been wondering why I had chosen to walk alongside a railway track, rather than visit the Botanic Gardens or some modern shopping centre.

"I love the Bogor countryside," I said. "I love the little houses."

"Better than the city," said Wardi.

We came to a cluster of little huts on top of a slope and I decided to take some photos. A cheery old man in a Tommy Cooper hat was seated in an armchair next to a slumbering cat and some cadmium orange cannas. Two boys were playing marbles. Above were tangles of electricity wires and a tall flowering rose of India. I got out my camera and looked through the lens. About twenty children had materialised from various alleys and they were pushing and shoving to get the best position in front of the camera. No sign of the old gentleman. He was hidden somewhere behind all these kids. There were whoops and yells and snorts. I took one photo and put my camera away.

"Hey mister," said a chunky lady with an aggressive face, "there’s a sick baby here."

"Where?" I asked.

"In the little house there," she said, pointing to a nearby one-roomed wooden hut.

It seemed like the sort of place where, in Britain, you might keep a lawnmower. While Wardi guarded Min, I stepped inside the tiny habitation. On the floor sat a young mother and a granny, and in front of them lay a baby, bluey-purple in colour, and struggling for air.

"How long has the baby been ill?" I asked.

"Five days," said the mum, who, on the surface, didn’t look particularly worried.

"The baby must go to a hospital immediately," I insisted. "Look, it’s blue because it can hardly breathe. Have you been to a doctor?"

"No," said the mum.

"We must go now," I said. "I’ll pay. OK?"

"Maybe we’ll go later," said the mum.

"When?" I asked her.

"Tomorrow."

"That’ll be too late. The baby’s nearly dead." I pointed at the blue little face.

Granny spoke for the first time. "We’ve been to the dukun. He gave us some medicine."

"The witch doctor has not got oxygen and a drip," I said, sarcastically. "The baby needs to be in a hospital. Why can’t we go now?"

"My husband’s not home yet," said the mum. "We’ll need to ask him."

"When does he get home?" I inquired.

"Late tonight," said the mum.

"Where is he now?"

"Far away," she said.

"We must go now to save the baby," I said loudly.

Granny spoke for a second time. "She doesn’t want to go."

It occurred to me that it is the conservatism of the poor that causes them so many of their problems. The elite are more adventurous.

I was not going to give up. I stood at the door. Then I waited outside with Wardi and Min, the latter giving me a worried look. I explained the situation to Wardi, who was apparently happy to let me take the lead in this situation. If he thought I was wasting my time he was not going to tell me. We waited and waited. I was getting hungry, as I supposed were Wardi and Min.

I couldn’t wait for ever, so I went back in.

"Shall we go to the hospital?" I said fairly gently. "We can ask the doctor what’s wrong. We don’t have to accept any medicine. Come on."

The mother picked up the blue baby and without any further words we set off towards my van. As we drove to the Red Cross hospital I just hoped the baby was not going to die on the way.

In the emergency room the doctor got the baby fitted up to a supply of oxygen.

"How long has the baby been ill?" he asked.

"Five days," I explained.

"It’s amazing it’s still alive," said the doctor. "It’s got tetanus. The midwife, or whoever delivered the baby, probably used dirty scissors. It’ll have to be admitted to the children’s ward."

The doctor spoke to the mother and granny and they now seemed resigned to the fact that one or other of them would have to stay with the baby in the hospital. I paid the bills, left money with the mother, explained that I would be back a week later, and then hurried off with Wardi and Min to get some fried chicken and chips.

That evening I met Fergus for dinner at the Meridien hotel where a meal costs as much as one week’s stay in the third class ward of the Red Cross hospital. The restaurant reminded me of a lounge on a luxury cruise liner.

"Elections coming up," said Fergus, as he began to cut up his omelette. "and that means you have to be a bit careful when there are street demonstrations."

"Would you advise staying off the main roads?" I said.

"When they’re all out parading, yes," said Fergus. "But if you do happen to get caught up in the middle of the green lot, remember to hold up one finger. That’s their sign. The yellows are two fingers and the reds three."

"I’ve seen lots of people holding up three fingers."

"And I’ve seen a few drivers holding up one finger," said Fergus.

"How democratic are these elections?"

"Well, let’s say that the President’s party, the yellows, always win."

"Things should be calmer than last year, when they had the Gulf War," I commented. "Lots of Indonesians seemed to be supporting Saddam."

"Which might seem odd," said Fergus, "because Saddam was put into power by the Americans and armed by the Americans. He was very much a CIA-Pentagon asset."

"I suppose that what’s changed is that Saddam’s now presenting himself as the champion of the Palestinians. That’s why he’s popular here, but not in the Pentagon."

"Coming back to the subject of Indonesia’s elections," said Fergus, "There’s no need to worry.

Most Indonesians are pretty easygoing about life. They like to be hospitable to all visitors. But do avoid the street demonstrations."

21 TWO WIVES TO SUPPORT

Because it was a Sunday and my driver’s day off, I had employed a driver from an agency, a young hollow-cheeked fellow who seemed a trifle nervous. I explained to him that I wanted a trouble free ride to the countryside and the city of Bogor. I asked him to avoid the political rally going on in the centre of Jakarta. It was May 1992 and we were in the middle of a general election campaign.

"Which party is having its parade today?" I asked the driver.

"The red party, PDI. Very big crowds," he said, as he crashed the gears.

"Well, be careful which route you choose to get to the toll road," I warned.

We left my leafy residential area, drove past markets and railway stations, skirted the offices around Jakarta’s Panin Centre, turned into Sudirman Boulevard, and drove straight into the middle of a mile-long procession.

Here they were: thousands and thousands of wild-eyed PDI supporters in control of the streets; they were draped in red, waving giant red flags, and screaming like Liverpool fans; some danced on the tops of buses and trucks, hired for the day; some rode noisy motorbikes; the most battle-hungry youths had masked their faces with blood-red scarves.

Now my driver and I were part of the parade but we were not wearing red and everyone else was.

At various road junctions, small groups of tough-looking soldiers and military police stood stony-faced, breathing in the traffic fumes, aware that they were outnumbered. Democracy was sometimes said to be a fragile thing, but so too was the police state. Indonesia had an army of about 400,000 but the population of Indonesia was over 200 million. What would happen if all the people united in opposition to the army?

"Turn left!" I said hoarsely, while trying to remember if I should be holding up one finger, or two. I thought two fingers seemed appropriate.

"We can’t turn left," said the driver, a touch nervously. "The army won’t let us."

"We’ll be here all day," I grumbled. "We’ve got to find a road out."

I wondered if the driver had done all this deliberately or if he only knew one route to the Bogor toll road. Even he looked anxious when burly chaps began thumping their fists against the side of our van. The driver held up three fingers and the thumping stopped.

The worst of it was that I had a more than urgent need to empty my bladder. Too much coffee and juice at breakfast meant that I was bursting. What I wanted was a quiet spot, away from prying eyes, but here I was surrounded by a large proportion of the population of Jakarta, and they all seemed to be staring into my vehicle. Surely there was a bush or a tree somewhere.

We inched our way down the broad boulevard as I crossed my legs and fingers. Sudirman seemed to go on for ever. Under the flyover at Semanggi, past the Sahid Jaya Hotel and on and on we went.

"Try turning left into that office complex," I urged.

"OK. What now?" replied the driver as we drove into a car park.

"Look for a back way out," I said.

Eventually, by way of the back streets of Menteng, we somehow reached the toll road to Bogor.

"Stop!" I ordered, five minutes after leaving the toll gates. "I need to get out to go to the toilet."

"Can’t stop," said the driver. "This is a toll road. The police don’t allow people to stop."

"Stop or I won’t pay you."

We skidded to a stop on the hard shoulder and I hurried across some grass to where the trees were. Alas, every square meter in this part of Java seems to have someone on it. Up a tree an old man was collecting fruit; to my left an old woman was hanging washing on top of some bushes; to my right three kids were taking a toddler for a walk. I crouched down and the peasant people politely looked away. At last I could breathe more easily and enjoy the journey.

On reaching Bogor and the area known as Batutulis, I visited the home of the blue baby. The child was now pink and healthy looking. I hoped it was not brain damaged by its days with inadequate oxygen.

"Have you been back to the hospital for a check up?" I said to the baby’s mum.

"Not yet."

"We’d better go now then."

At the Red Cross hospital the doctor examined the child and issued some more medicine. The doctor assured me that the baby was fine.

My next stop was Bogor’s mental hospital to see Chong, the young man who had been a heap of skin and bones when I had found him lying in the street. Chong had been moved to a different ward as he had put on weight and looked human again. It was a locked ward, a single storey building with a certain amount of pealing white paint and green mould. I took Chong for a short walk but could not get any conversation out of him. I supposed that being mentally backward, having been rejected by his family, and being a penniless Chinese Indonesian, he had the cards stacked against him.

In the mental hospital’s children’s ward, John and Daud were again tied up. I was allowed to take them for a walk to the shop where we bought more milk and biscuits.

"Why do you keep these kids tied up when there’s a garden here for them to play in?" I asked the well fed female nurse. She was wearing an expensive watch and a necklace with a little crucifix.

"They’re idiots," she said, with what was either a smile or a smirk.

In their impoverished hamlet in Bogor Baru, little Andi was still looking malnourished and Asep was still pale. Asep gave me some more receipts for his TB medicine, which I examined carefully.

"These receipts only cover twenty thousand rupiahs. What about the other hundred thousand?" I asked.

"I don’t know," said Asep, smiling innocently.

"Have you still got the medicine? I gave you enough money to last a month."

"The medicine’s finished," explained Asep.

"You’d better go now to get some more. Here’s money to last a month and I must have receipts to cover the full amount. It’s not to be used for school fees or clothes or televisions."

I thought of what more than one expat had said to me about some of the locals. ‘They are like children.’

I went to see Dian, sister of Melati and Tikus, in their little house near the centre of Bogor. Dian had a smart new top and skirt.

"Have you got a receipt for your TB medicine?" I asked Dian.

"I lost it," she said.

"Have you got the TB medicine?"

"It’s finished."

"It can’t be," I complained. "I gave you enough money for one month. You know you have to take the medicine for six months to a year, or even longer?"

"Yes."

"We’d better go now to the doctor," I said, very crossly. "I’ll come with you to make sure we get the medicine." I felt more than ever that it was like dealing with foolish and naughty primary school kids, and I began grinding my teeth. But at least I was learning more about the Third World and how the world worked. And, I supposed, I was having a bit of an adventure.

Having dealt with Dian, I took a stroll through a section of Bogor near Empang. It was an area I had not been to before and I had a feeling of pleasant excitement. I dawdled contentedly past an old church with a sharp steeple and next to it a large Christian school painted in dark colours; I wandered down a long flight of very steep steps decorated with colourful graffiti; I roamed along a dark river bank. The air was hot and humid and filled with the scent of Peacock Flowers and urine. The narrow tree-lined lanes were crowded with street vendors with poles over their shoulders; some poles supported pots of steaming soup and noodles, some carried flashing mirrors, and some bore light tables and chairs. Children were pulling along home-made toy cars attached to sticks or attempting to play games of football. I could see that West Java was over populated. There were babies and pregnant women at every street corner, at every door, and in every room, or so it seemed.

I turned a corner and there, seated at a snack stall, was a girl with the most beautiful face I had ever seen. Shall I compare her to a summer’s day or a day during the rainy season? How come this face began, according to some versions of Big Bang theory, with nothingness? Billions of years ago, time and matter apparently didn’t exist. Then bang, the universe was created, leading to this lovely visage. I was giddy just thinking about it. Were there even more beautiful faces in some parallel universes?

You can’t stare forever at dark dilated eyes, soft curving cheeks and cute kissable lips. It gets boring.

So I continued my journey. Having passed a happy group of little children outside a green roofed mosque, I climbed up and down various steep concrete paths, and eventually descended to a muddy brown river sided by a terrace of wooden houses. Outside one tumbledown shack sat a young woman of striking appearance. She had once been beautiful but now she looked wasted and grey.

"Hello," I said, "are you well?"

"Not well," she said, giving me a sweet smile. "I have TB."

"Are you getting any medicine?" I asked.

"No. I used to take the pills."

"How long ago?"

"Three years ago."

"And you’re not yet better?"

"Not yet."

I went with her to Bogor’s Menteng hospital. On the way she was struggling for breath.

"It doesn’t look good," said the doctor, in English, holding up an x-ray. "Suti says she’s taken the pills, off and on, over many years. The trouble is that if they stop taking the medicine before they’re cured, then the disease becomes drug resistant. Over the years her organs have been seriously damaged. I’m afraid she won’t last long."

"Has she got a family?"

"She’s single and lives with her mother. The mother is apparently fit."

I arranged for Suti to get regular supplies of medicine, but learnt some months later that she had died. What a mixture Bogor was: the scent of flowers and the scent of death.

Next afternoon, Min was in good spirits when I collected him from Wisma Utara.

"Has his family been to see him?" I asked Joan, anxiously.

"No, but it’s a long way for them to travel," she said.

"It’s odd that they haven’t been to see him," I commented. I hoped this was not a sign that his family were indifferent to Min’s welfare.

"I’m taking him to visit his home now," I explained. "We’ll be back after supper."

On reaching Min’s house in Teluk Gong, Min was in a state of high excitement. Min’s mother, Wati, seemed a little subdued in her greeting. There was no sign of Min’s older brother Wardi. Maybe he was at work. Min’s brother in law, Gani, was delegated to accompany Min and I on a walk through the slums.

We squeezed past the huts of some collectors of rubbish and stooped under washing strung between windows on either side of our narrow path. The dripping shirts and blouses , silhouetted against a darkening blue sky, added a touch of colour to an otherwise grey landscape. We reached a rubbish tip and turned left into a dark alley crowded as always with people of all shapes and sizes. Looking in the open doors of the wooden houses we could see children sitting on mats and doing homework, men preparing sate to be sold later from carts, and women picking the nits out of each other’s hair. When we reached a house where children were watching a cartoon on TV, Min decided to enter the house and join the youngsters on the floor. Nobody objected. Gani waited patiently for several minutes before gently taking Min by the hand and leading him back out into the narrow street.

One wooden house on stilts had two little stick-insect children at the door.

"What are your names?" I asked the two kids, who looked about seven years old.

"Sani," whispered the boy.

"Indra," whispered the girl.

"They look too thin," I said to their big-boned mother, who had come to the door. "Would you like them to see a doctor?"

"They’ve been to a doctor and had an x-ray," said the mum, "but we’ve no money for the medicine."

"Would you like to come with me to a clinic?" I asked. "It’s a good clinic, in the centre of the city. It’s the one I use myself."

"I’ll ask my husband," she said. A smiling little man appeared from inside the house and a consultation took place involving mother, father, Gani and members of the small crowd which had gathered. There was agreement that a trip into town would be a good idea.

We took Sani, Indra, their mum and their skinny dad to see my doctor at Jakarta’s Kuningan Medical centre, an upmarket clinic with carpets, exotic pot plants, and glass tables covered in copies of Moneyweek.

"It’s TB," said Doctor Handoko, a cheerful, middle-aged Chinese Indonesian. "I’ll give them the usual cocktail of drugs."

Doctor Handoko seemed to be in a bit of a rush. I suppose he was not used to dealing with patients from the slums, people who arrived in dirty plastic sandals and ragged shirts.

Back in my van I asked Sani and Indra’s father what he did for a living.

"I’m a driver," he explained, grinning in friendly fashion.

"Who do you work for?" I inquired.

"A rich Chinese Indonesian," he said.

"How much do you get a month?"

"Eighty thousand rupiahs."

"That’s about twenty pounds sterling," I said. "That’s less than I’ve just paid the Kuningan Medical centre for the medicine and a ten minute consultation."

"He’s got two wives to support," whispered Min’s brother in law. "Two wives and two lots of children."

I could see why Sani and Indra were thin.

I could also see that neither Wati, Min’s mum, nor Wardi, Min’s big brother, had come with us.

"Which party is having its parade today?" I asked the driver.

"The red party, PDI. Very big crowds," he said, as he crashed the gears.

"Well, be careful which route you choose to get to the toll road," I warned.

We left my leafy residential area, drove past markets and railway stations, skirted the offices around Jakarta’s Panin Centre, turned into Sudirman Boulevard, and drove straight into the middle of a mile-long procession.

Here they were: thousands and thousands of wild-eyed PDI supporters in control of the streets; they were draped in red, waving giant red flags, and screaming like Liverpool fans; some danced on the tops of buses and trucks, hired for the day; some rode noisy motorbikes; the most battle-hungry youths had masked their faces with blood-red scarves.

Now my driver and I were part of the parade but we were not wearing red and everyone else was.

At various road junctions, small groups of tough-looking soldiers and military police stood stony-faced, breathing in the traffic fumes, aware that they were outnumbered. Democracy was sometimes said to be a fragile thing, but so too was the police state. Indonesia had an army of about 400,000 but the population of Indonesia was over 200 million. What would happen if all the people united in opposition to the army?

"Turn left!" I said hoarsely, while trying to remember if I should be holding up one finger, or two. I thought two fingers seemed appropriate.

"We can’t turn left," said the driver, a touch nervously. "The army won’t let us."

"We’ll be here all day," I grumbled. "We’ve got to find a road out."

I wondered if the driver had done all this deliberately or if he only knew one route to the Bogor toll road. Even he looked anxious when burly chaps began thumping their fists against the side of our van. The driver held up three fingers and the thumping stopped.

The worst of it was that I had a more than urgent need to empty my bladder. Too much coffee and juice at breakfast meant that I was bursting. What I wanted was a quiet spot, away from prying eyes, but here I was surrounded by a large proportion of the population of Jakarta, and they all seemed to be staring into my vehicle. Surely there was a bush or a tree somewhere.

We inched our way down the broad boulevard as I crossed my legs and fingers. Sudirman seemed to go on for ever. Under the flyover at Semanggi, past the Sahid Jaya Hotel and on and on we went.

"Try turning left into that office complex," I urged.

"OK. What now?" replied the driver as we drove into a car park.

"Look for a back way out," I said.

Eventually, by way of the back streets of Menteng, we somehow reached the toll road to Bogor.

"Stop!" I ordered, five minutes after leaving the toll gates. "I need to get out to go to the toilet."

"Can’t stop," said the driver. "This is a toll road. The police don’t allow people to stop."

"Stop or I won’t pay you."

We skidded to a stop on the hard shoulder and I hurried across some grass to where the trees were. Alas, every square meter in this part of Java seems to have someone on it. Up a tree an old man was collecting fruit; to my left an old woman was hanging washing on top of some bushes; to my right three kids were taking a toddler for a walk. I crouched down and the peasant people politely looked away. At last I could breathe more easily and enjoy the journey.

On reaching Bogor and the area known as Batutulis, I visited the home of the blue baby. The child was now pink and healthy looking. I hoped it was not brain damaged by its days with inadequate oxygen.

"Have you been back to the hospital for a check up?" I said to the baby’s mum.

"Not yet."

"We’d better go now then."

At the Red Cross hospital the doctor examined the child and issued some more medicine. The doctor assured me that the baby was fine.

My next stop was Bogor’s mental hospital to see Chong, the young man who had been a heap of skin and bones when I had found him lying in the street. Chong had been moved to a different ward as he had put on weight and looked human again. It was a locked ward, a single storey building with a certain amount of pealing white paint and green mould. I took Chong for a short walk but could not get any conversation out of him. I supposed that being mentally backward, having been rejected by his family, and being a penniless Chinese Indonesian, he had the cards stacked against him.

In the mental hospital’s children’s ward, John and Daud were again tied up. I was allowed to take them for a walk to the shop where we bought more milk and biscuits.

"Why do you keep these kids tied up when there’s a garden here for them to play in?" I asked the well fed female nurse. She was wearing an expensive watch and a necklace with a little crucifix.

"They’re idiots," she said, with what was either a smile or a smirk.

In their impoverished hamlet in Bogor Baru, little Andi was still looking malnourished and Asep was still pale. Asep gave me some more receipts for his TB medicine, which I examined carefully.

"These receipts only cover twenty thousand rupiahs. What about the other hundred thousand?" I asked.

"I don’t know," said Asep, smiling innocently.

"Have you still got the medicine? I gave you enough money to last a month."

"The medicine’s finished," explained Asep.

"You’d better go now to get some more. Here’s money to last a month and I must have receipts to cover the full amount. It’s not to be used for school fees or clothes or televisions."

I thought of what more than one expat had said to me about some of the locals. ‘They are like children.’

I went to see Dian, sister of Melati and Tikus, in their little house near the centre of Bogor. Dian had a smart new top and skirt.

"Have you got a receipt for your TB medicine?" I asked Dian.

"I lost it," she said.

"Have you got the TB medicine?"

"It’s finished."

"It can’t be," I complained. "I gave you enough money for one month. You know you have to take the medicine for six months to a year, or even longer?"

"Yes."

"We’d better go now to the doctor," I said, very crossly. "I’ll come with you to make sure we get the medicine." I felt more than ever that it was like dealing with foolish and naughty primary school kids, and I began grinding my teeth. But at least I was learning more about the Third World and how the world worked. And, I supposed, I was having a bit of an adventure.

Having dealt with Dian, I took a stroll through a section of Bogor near Empang. It was an area I had not been to before and I had a feeling of pleasant excitement. I dawdled contentedly past an old church with a sharp steeple and next to it a large Christian school painted in dark colours; I wandered down a long flight of very steep steps decorated with colourful graffiti; I roamed along a dark river bank. The air was hot and humid and filled with the scent of Peacock Flowers and urine. The narrow tree-lined lanes were crowded with street vendors with poles over their shoulders; some poles supported pots of steaming soup and noodles, some carried flashing mirrors, and some bore light tables and chairs. Children were pulling along home-made toy cars attached to sticks or attempting to play games of football. I could see that West Java was over populated. There were babies and pregnant women at every street corner, at every door, and in every room, or so it seemed.

I turned a corner and there, seated at a snack stall, was a girl with the most beautiful face I had ever seen. Shall I compare her to a summer’s day or a day during the rainy season? How come this face began, according to some versions of Big Bang theory, with nothingness? Billions of years ago, time and matter apparently didn’t exist. Then bang, the universe was created, leading to this lovely visage. I was giddy just thinking about it. Were there even more beautiful faces in some parallel universes?

You can’t stare forever at dark dilated eyes, soft curving cheeks and cute kissable lips. It gets boring.

So I continued my journey. Having passed a happy group of little children outside a green roofed mosque, I climbed up and down various steep concrete paths, and eventually descended to a muddy brown river sided by a terrace of wooden houses. Outside one tumbledown shack sat a young woman of striking appearance. She had once been beautiful but now she looked wasted and grey.

"Hello," I said, "are you well?"

"Not well," she said, giving me a sweet smile. "I have TB."

"Are you getting any medicine?" I asked.

"No. I used to take the pills."

"How long ago?"

"Three years ago."

"And you’re not yet better?"

"Not yet."

I went with her to Bogor’s Menteng hospital. On the way she was struggling for breath.

"It doesn’t look good," said the doctor, in English, holding up an x-ray. "Suti says she’s taken the pills, off and on, over many years. The trouble is that if they stop taking the medicine before they’re cured, then the disease becomes drug resistant. Over the years her organs have been seriously damaged. I’m afraid she won’t last long."

"Has she got a family?"

"She’s single and lives with her mother. The mother is apparently fit."

I arranged for Suti to get regular supplies of medicine, but learnt some months later that she had died. What a mixture Bogor was: the scent of flowers and the scent of death.

Next afternoon, Min was in good spirits when I collected him from Wisma Utara.

"Has his family been to see him?" I asked Joan, anxiously.

"No, but it’s a long way for them to travel," she said.

"It’s odd that they haven’t been to see him," I commented. I hoped this was not a sign that his family were indifferent to Min’s welfare.

"I’m taking him to visit his home now," I explained. "We’ll be back after supper."

On reaching Min’s house in Teluk Gong, Min was in a state of high excitement. Min’s mother, Wati, seemed a little subdued in her greeting. There was no sign of Min’s older brother Wardi. Maybe he was at work. Min’s brother in law, Gani, was delegated to accompany Min and I on a walk through the slums.

We squeezed past the huts of some collectors of rubbish and stooped under washing strung between windows on either side of our narrow path. The dripping shirts and blouses , silhouetted against a darkening blue sky, added a touch of colour to an otherwise grey landscape. We reached a rubbish tip and turned left into a dark alley crowded as always with people of all shapes and sizes. Looking in the open doors of the wooden houses we could see children sitting on mats and doing homework, men preparing sate to be sold later from carts, and women picking the nits out of each other’s hair. When we reached a house where children were watching a cartoon on TV, Min decided to enter the house and join the youngsters on the floor. Nobody objected. Gani waited patiently for several minutes before gently taking Min by the hand and leading him back out into the narrow street.

One wooden house on stilts had two little stick-insect children at the door.

"What are your names?" I asked the two kids, who looked about seven years old.

"Sani," whispered the boy.

"Indra," whispered the girl.

"They look too thin," I said to their big-boned mother, who had come to the door. "Would you like them to see a doctor?"

"They’ve been to a doctor and had an x-ray," said the mum, "but we’ve no money for the medicine."

"Would you like to come with me to a clinic?" I asked. "It’s a good clinic, in the centre of the city. It’s the one I use myself."

"I’ll ask my husband," she said. A smiling little man appeared from inside the house and a consultation took place involving mother, father, Gani and members of the small crowd which had gathered. There was agreement that a trip into town would be a good idea.

We took Sani, Indra, their mum and their skinny dad to see my doctor at Jakarta’s Kuningan Medical centre, an upmarket clinic with carpets, exotic pot plants, and glass tables covered in copies of Moneyweek.

"It’s TB," said Doctor Handoko, a cheerful, middle-aged Chinese Indonesian. "I’ll give them the usual cocktail of drugs."

Doctor Handoko seemed to be in a bit of a rush. I suppose he was not used to dealing with patients from the slums, people who arrived in dirty plastic sandals and ragged shirts.

Back in my van I asked Sani and Indra’s father what he did for a living.

"I’m a driver," he explained, grinning in friendly fashion.

"Who do you work for?" I inquired.

"A rich Chinese Indonesian," he said.

"How much do you get a month?"

"Eighty thousand rupiahs."

"That’s about twenty pounds sterling," I said. "That’s less than I’ve just paid the Kuningan Medical centre for the medicine and a ten minute consultation."

"He’s got two wives to support," whispered Min’s brother in law. "Two wives and two lots of children."

I could see why Sani and Indra were thin.

I could also see that neither Wati, Min’s mum, nor Wardi, Min’s big brother, had come with us.

22. SUKABUMI

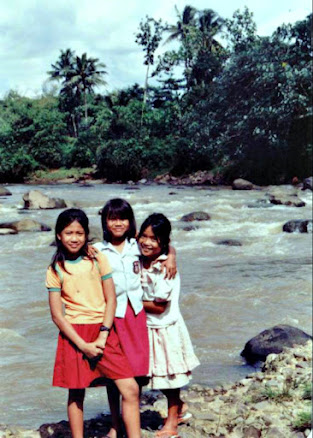

The beginning of the May half term found me exploring the area around the small Sundanese hill town of Sukabumi, at the foot of the volcanoes Gede and Pangrango. Sukabumi, which lies between Bandung and Bogor, has more earthquakes and tremors than anywhere else in Indonesia, so I was watching out for signs of dogs or chickens behaving strangely. A major earthquake in 1972 killed over two thousand people in the region.

Having left my vehicle and driver on a quiet country road, I followed a path which ran below lofty flowering trees and above a muddy river. I was looking out anxiously for snakes, wild monkeys or even leopards, but all I saw, fortunately, were big blue dragonflies and orange-yellow butterflies flitting in and out of patches of brilliant dusty light and jet-black shadow. When I took a left turn and began to descend towards the river, I could hear splashing sounds and giggles.

"Hey mister," called a young voice behind me, "you can’t go down there."

I turned and saw two grinning boys, both aged about thirteen, and both dressed in threadbare shirts and shorts.

"Why not," I asked them.

"Women bathing," said the taller one, eyes gleaming with a hint of mischief.

"Ah," I said.

At that moment a young woman wrapped in towels, and carrying a basin full of damp clothes, came up from the river and hurried past me. She had Spanish good-looks and an enigmatic smile.

I returned to the main path and was followed by the two boys who introduced themselves as Hari and Dani.

"Are you going to school?" I asked.

"No," said Hari, with an amiable smile. "No money."

"You have to pay for school?"

"Yes. And for uniforms and books and outings," said Dani, putting on a serious face.

"Where are you going, mister?" asked Hari.

"Jalan jalan," I said. Just out for a walk.

"Ikut?" asked Hari. Follow you?

"OK," I replied, pleased to have some company.

Having passed some damp looking huts inhabited by grey faced people, and a stretch of green meadow which gave us views of the smudgy blue mountains, we arrived at a bridge made from bamboo. In the river below us, happy boys were swimming, washing and defecating. I could also see one child cleaning his teeth. This was a fast flowing river and not too crowded, but I imagined that, back in the overpopulated city of Bogor, the use of the river as a bathroom was a cause of that city’s ever-present typhoid.

Before I could say the word ‘salmonellosis’, Hari and Dani had stripped off their shirts and jumped feet first from the bridge into the river. Dripping with water, they then clambered back up to join me on the bridge.

As we continued our ramble through the hot sunny valley, steam rose from the boys’ wet clothes. I noticed that shirtless Hari’s ribs stuck out.

"How often do you eat each day?" I asked him.

"Sometimes only once a day."

"What work does your father do?"

"He doesn’t work," said Hari. "My mum works in Jakarta."

"What work?"

"She’s a maid."

"Who looks after you? Who does the cooking and washing while your mum’s away in Jakarta?"

"My big sister," said Hari.

"What about your father?" I asked Dani, who was also undernourished.

"Coolie," he said

We came to a grand mansion in large grounds with neat lawns. Three large station-wagons were parked outside the pillared entrance.

"Who lives here?" I asked.

"Haji Amar," said Hari, sounding respectful.

"What does he do?"

"He was a judge," explained Dani. "He owns the land around here."

A judge would earn about one hundred and fifty pounds sterling a month. But then he might also receive the occasional gift.

"You’ve been useful guides," I said. "Now I’m heading back to Sukabumi for something to eat."

"Smoking, mister?" said Hari, rather shyly.

"Smoking?" I asked. Then I realised they wanted cigarettes.

I gave them a few coins.

"For food," I insisted.

"Thanks, mister!" they said, taking the money politely and skipping off happily.

Back in Sukabumi I walked around the potholed streets. In the open-air market, women with fat legs squatted beside their piles of sweet potatoes and skinny youths were selling cigarettes from baskets hung around their necks. On a street where the outside walls were black with fungus and mould I found a dark little cafe. I dined on biscuits and cola.

After a night at a clean, air-conditioned hotel in the nearby hill resort of Selabintana, a hotel apparently owned by the army, I motored to Pelabuhan Ratu on the South coast. I booked into the Samudra Beach Hotel.

Walking East from the harbour I took photos of fishing boats and palm trees and enjoyed the salty sea breeze. Near some rice fields and a bat cave, I stopped to talk to a barefoot woman carrying a girl aged about seven. The girl, called Marni, looked pale yellow and her stomach was swollen.

"Is she sick?" I asked.

"She’s been ill for years," said the mother, whose own body was podgy and pale.

"Have you been to the local hospital?"

"My husband’s dead. I’ve no money."

We reached the simple little hospital in five minutes and consulted an earnest young doctor who did a blood test.

"It looks like Thalassaemia," he said. "That’s anaemia caused by defects in the genes that make haemoglobin. It’s inherited and quite common in this part of Indonesia. The girl’s father seems to have died from it."

"What can be done?" I asked.

"She’ll need repeated blood transfusions," said the doctor, in English. "We could get some blood by tomorrow from Sukabumi. Kids like Marni don’t always live too long. It depends on the type of Thalassaemia and on the treatment."

The doctor explained some of this to the mother.

"Does she want Marni to have a blood transfusion?" I inquired.

"No," said the doctor. "She says the girl doesn’t want a transfusion."

The girl was quietly weeping.

"But what about the mother?" I said.

"She says no."

"Are blood transfusions safe?" I asked.

"Blood transfusions can lead to a build up of iron, which can be fatal."

"What about AIDS?"

"That’s another risk."

The mother was determined that there should not be a transfusion, and maybe she was right, but I left her some money to pay for treatment in case she changed her mind.

I walked West from the harbour and after a few miles came to a wooden restaurant built on stilts. An old man appeared from inside and invited me to have a beer and some fresh fish. As I enjoyed my feast, I watched the surf roar in towards the blue and yellow fishing boats and thought that this could be paradise, if it wasn’t that the south coast suffered from poor roads and malaria.

Next morning, before returning to Jakarta via Bogor, I returned to Marni’s one room shack but there was no one there.

"The mother’s out working in the fields," said a middle aged man with strong muscles and thick dark hair, "I’m the community chief, the RT, and I’m related to Marni."

"I was going to give the mother some money for food," I said.

"Give it to me and I’ll make sure she gets it," said the man.

If he was the RT, the community chief, maybe he would be helpful. I gave him the money.

I stopped off in Bogor, and having collected hospital receipts from tubercular Asep, took a walk through some woodland beyond Bogor Baru. There were clusters of dingy wooden houses, steep ascents and descents on narrow paths, smelly goats in wooden enclosures, clumps of bamboo and occasional clouds of mosquitoes. The people here looked undernourished and were dressed in patched and tattered clothing.

Outside a cobwebbed wooden hovel, shaded by dark trees, sat a middle-aged woman and a boy aged about twelve. They gave me a tired but friendly smile and, intrigued by their appearance, I decided to introduce myself. The woman, whose name was Ciah, was yellow skinned and had the shrivelled look of the poorest of the poor. The boy, called Agosto, had a purple scar on his thigh and a sad look on his face.

"What do you do for a living?" I asked Ciah.

"Wash clothes," she replied in a weary voice.

"How much do you get?"

"About thirty thousand rupiahs a month." This was less than ten pounds sterling a month.

"Does you husband work in the fields?"

"My husband’s dead," she replied, smiling an embarrassed smile.

"My mother is sick," said Agosto.

"I get very tired," said Ciah.

When I suggested a trip to the hospital for a check-up, Ciah agreed immediately.

At the Menteng Hospital, the doctor diagnosed hepatitis and Ciah was admitted to the third class ward. Agosto sat by her bedside. He had a handsome little face but there was a look in his big dark eyes that spoke of lost hopes and despair. Not for him fishing trips with dad or games of football at school.

On returning to Jakarta, the first place I visited was Wisma Utara. Min was having one of his down days and refused to take my hand.

"Have his parents been to visit him?" I asked Joan.

"Not yet."

I thought of Hari, the kid in Sukabumi, who presumably didn’t see too much of his mother. Maybe Min’s family were all busy working.

"I’m off for a walk with Min," I explained. "I want to see if Iwan’s back yet to get his leprosy medicine."

Iwan was not back.

"He’s still at his kampung in Karawang," said a thin little man, who was standing beside a rubbish cart. He wore shabby clothes and had a grin that suggested possible slyness or a lack of intelligence.

"Do you know his address?" I asked.

"Yes. I’m Iwan’s uncle," said the man.

"I’m worried," I said, "because he’s not had his leprosy medicine for weeks and weeks."

"I could go and bring him back," said the man.

"Good. When can you go?"

"Tonight."

I gave him the money for the bus.

Hamid, the runaway I had found in Pasar Mayestic, had not been visited for some time, so I drove with Min to Hamid’s grandmother’s mansion.

"How’s Hamid?" I asked granny, when she came to the door.

"He’s run away again," said the tired looking woman. "Probably gone back to the market."

"What went wrong?" I asked.

"He doesn’t like school."

I returned with Min to Wisma Utara. At least Min was in a safe place.

While enjoying a cup of coffee in the staffroom, I got talking to Carmen about the lives of Indonesian children. I told Carmen about Hamid in Pasar Mayestic, Marni the thalassaemia girl in Pelabuhan Ratu, sad Agosto in Bogor and Iwan the boy with leprosy.

"Hamid looks like a survivor," I said. "He must have guts to survive in Pasar Mayestic. But Marni and Agosto look near to giving up; and Iwan is heading for disaster if he doesn’t take his leprosy medicine."

"You know at the beginning of the 20th Century," said Carmen, "life was rough for some British children working on farms. I was reading about a child called Angus who had to work like a slave when he was a child. He had to be tough to stay alive"

"I suppose children were forced to leave school at a young age," I commented.

"Angus’s parents were poor and gave him to a farmer; they sold him," said Carmen. "Angus had to work seven days a week from early morning until late at night. He could be beaten if he complained. He lived in a freezing cold building with no toilet or bath and he’d be fed scraps. Britain this century. At least in Indonesia it’s warm and you can bathe in a river."

"Selabintana was cold at night!"

I told Carmen about the judge’s house.

"Maybe he has a rich wife," she said. "Anyway, people say there’s just as much corruption in Britain and Europe as in Indonesia."

"I suppose in the West it’s more cleverly covered up," I said.

Having left my vehicle and driver on a quiet country road, I followed a path which ran below lofty flowering trees and above a muddy river. I was looking out anxiously for snakes, wild monkeys or even leopards, but all I saw, fortunately, were big blue dragonflies and orange-yellow butterflies flitting in and out of patches of brilliant dusty light and jet-black shadow. When I took a left turn and began to descend towards the river, I could hear splashing sounds and giggles.

"Hey mister," called a young voice behind me, "you can’t go down there."

I turned and saw two grinning boys, both aged about thirteen, and both dressed in threadbare shirts and shorts.

"Why not," I asked them.

"Women bathing," said the taller one, eyes gleaming with a hint of mischief.

"Ah," I said.

At that moment a young woman wrapped in towels, and carrying a basin full of damp clothes, came up from the river and hurried past me. She had Spanish good-looks and an enigmatic smile.

I returned to the main path and was followed by the two boys who introduced themselves as Hari and Dani.

"Are you going to school?" I asked.

"No," said Hari, with an amiable smile. "No money."

"You have to pay for school?"

"Yes. And for uniforms and books and outings," said Dani, putting on a serious face.

"Where are you going, mister?" asked Hari.

"Jalan jalan," I said. Just out for a walk.

"Ikut?" asked Hari. Follow you?

"OK," I replied, pleased to have some company.

Having passed some damp looking huts inhabited by grey faced people, and a stretch of green meadow which gave us views of the smudgy blue mountains, we arrived at a bridge made from bamboo. In the river below us, happy boys were swimming, washing and defecating. I could also see one child cleaning his teeth. This was a fast flowing river and not too crowded, but I imagined that, back in the overpopulated city of Bogor, the use of the river as a bathroom was a cause of that city’s ever-present typhoid.

Before I could say the word ‘salmonellosis’, Hari and Dani had stripped off their shirts and jumped feet first from the bridge into the river. Dripping with water, they then clambered back up to join me on the bridge.

As we continued our ramble through the hot sunny valley, steam rose from the boys’ wet clothes. I noticed that shirtless Hari’s ribs stuck out.

"How often do you eat each day?" I asked him.

"Sometimes only once a day."

"What work does your father do?"

"He doesn’t work," said Hari. "My mum works in Jakarta."

"What work?"

"She’s a maid."

"Who looks after you? Who does the cooking and washing while your mum’s away in Jakarta?"

"My big sister," said Hari.

"What about your father?" I asked Dani, who was also undernourished.

"Coolie," he said

We came to a grand mansion in large grounds with neat lawns. Three large station-wagons were parked outside the pillared entrance.

"Who lives here?" I asked.

"Haji Amar," said Hari, sounding respectful.

"What does he do?"

"He was a judge," explained Dani. "He owns the land around here."

A judge would earn about one hundred and fifty pounds sterling a month. But then he might also receive the occasional gift.

"You’ve been useful guides," I said. "Now I’m heading back to Sukabumi for something to eat."

"Smoking, mister?" said Hari, rather shyly.

"Smoking?" I asked. Then I realised they wanted cigarettes.

I gave them a few coins.

"For food," I insisted.

"Thanks, mister!" they said, taking the money politely and skipping off happily.

Back in Sukabumi I walked around the potholed streets. In the open-air market, women with fat legs squatted beside their piles of sweet potatoes and skinny youths were selling cigarettes from baskets hung around their necks. On a street where the outside walls were black with fungus and mould I found a dark little cafe. I dined on biscuits and cola.

After a night at a clean, air-conditioned hotel in the nearby hill resort of Selabintana, a hotel apparently owned by the army, I motored to Pelabuhan Ratu on the South coast. I booked into the Samudra Beach Hotel.

Walking East from the harbour I took photos of fishing boats and palm trees and enjoyed the salty sea breeze. Near some rice fields and a bat cave, I stopped to talk to a barefoot woman carrying a girl aged about seven. The girl, called Marni, looked pale yellow and her stomach was swollen.

"Is she sick?" I asked.

"She’s been ill for years," said the mother, whose own body was podgy and pale.

"Have you been to the local hospital?"

"My husband’s dead. I’ve no money."

We reached the simple little hospital in five minutes and consulted an earnest young doctor who did a blood test.

"It looks like Thalassaemia," he said. "That’s anaemia caused by defects in the genes that make haemoglobin. It’s inherited and quite common in this part of Indonesia. The girl’s father seems to have died from it."

"What can be done?" I asked.

"She’ll need repeated blood transfusions," said the doctor, in English. "We could get some blood by tomorrow from Sukabumi. Kids like Marni don’t always live too long. It depends on the type of Thalassaemia and on the treatment."

The doctor explained some of this to the mother.

"Does she want Marni to have a blood transfusion?" I inquired.

"No," said the doctor. "She says the girl doesn’t want a transfusion."

The girl was quietly weeping.

"But what about the mother?" I said.

"She says no."

"Are blood transfusions safe?" I asked.

"Blood transfusions can lead to a build up of iron, which can be fatal."

"What about AIDS?"

"That’s another risk."

The mother was determined that there should not be a transfusion, and maybe she was right, but I left her some money to pay for treatment in case she changed her mind.

I walked West from the harbour and after a few miles came to a wooden restaurant built on stilts. An old man appeared from inside and invited me to have a beer and some fresh fish. As I enjoyed my feast, I watched the surf roar in towards the blue and yellow fishing boats and thought that this could be paradise, if it wasn’t that the south coast suffered from poor roads and malaria.

Next morning, before returning to Jakarta via Bogor, I returned to Marni’s one room shack but there was no one there.

"The mother’s out working in the fields," said a middle aged man with strong muscles and thick dark hair, "I’m the community chief, the RT, and I’m related to Marni."

"I was going to give the mother some money for food," I said.

"Give it to me and I’ll make sure she gets it," said the man.

If he was the RT, the community chief, maybe he would be helpful. I gave him the money.

I stopped off in Bogor, and having collected hospital receipts from tubercular Asep, took a walk through some woodland beyond Bogor Baru. There were clusters of dingy wooden houses, steep ascents and descents on narrow paths, smelly goats in wooden enclosures, clumps of bamboo and occasional clouds of mosquitoes. The people here looked undernourished and were dressed in patched and tattered clothing.

Outside a cobwebbed wooden hovel, shaded by dark trees, sat a middle-aged woman and a boy aged about twelve. They gave me a tired but friendly smile and, intrigued by their appearance, I decided to introduce myself. The woman, whose name was Ciah, was yellow skinned and had the shrivelled look of the poorest of the poor. The boy, called Agosto, had a purple scar on his thigh and a sad look on his face.

"What do you do for a living?" I asked Ciah.

"Wash clothes," she replied in a weary voice.

"How much do you get?"

"About thirty thousand rupiahs a month." This was less than ten pounds sterling a month.

"Does you husband work in the fields?"

"My husband’s dead," she replied, smiling an embarrassed smile.

"My mother is sick," said Agosto.

"I get very tired," said Ciah.

When I suggested a trip to the hospital for a check-up, Ciah agreed immediately.

At the Menteng Hospital, the doctor diagnosed hepatitis and Ciah was admitted to the third class ward. Agosto sat by her bedside. He had a handsome little face but there was a look in his big dark eyes that spoke of lost hopes and despair. Not for him fishing trips with dad or games of football at school.

On returning to Jakarta, the first place I visited was Wisma Utara. Min was having one of his down days and refused to take my hand.

"Have his parents been to visit him?" I asked Joan.

"Not yet."

I thought of Hari, the kid in Sukabumi, who presumably didn’t see too much of his mother. Maybe Min’s family were all busy working.

"I’m off for a walk with Min," I explained. "I want to see if Iwan’s back yet to get his leprosy medicine."

Iwan was not back.

"He’s still at his kampung in Karawang," said a thin little man, who was standing beside a rubbish cart. He wore shabby clothes and had a grin that suggested possible slyness or a lack of intelligence.

"Do you know his address?" I asked.

"Yes. I’m Iwan’s uncle," said the man.

"I’m worried," I said, "because he’s not had his leprosy medicine for weeks and weeks."

"I could go and bring him back," said the man.

"Good. When can you go?"

"Tonight."

I gave him the money for the bus.

Hamid, the runaway I had found in Pasar Mayestic, had not been visited for some time, so I drove with Min to Hamid’s grandmother’s mansion.

"How’s Hamid?" I asked granny, when she came to the door.

"He’s run away again," said the tired looking woman. "Probably gone back to the market."

"What went wrong?" I asked.

"He doesn’t like school."

I returned with Min to Wisma Utara. At least Min was in a safe place.

While enjoying a cup of coffee in the staffroom, I got talking to Carmen about the lives of Indonesian children. I told Carmen about Hamid in Pasar Mayestic, Marni the thalassaemia girl in Pelabuhan Ratu, sad Agosto in Bogor and Iwan the boy with leprosy.

"Hamid looks like a survivor," I said. "He must have guts to survive in Pasar Mayestic. But Marni and Agosto look near to giving up; and Iwan is heading for disaster if he doesn’t take his leprosy medicine."

"You know at the beginning of the 20th Century," said Carmen, "life was rough for some British children working on farms. I was reading about a child called Angus who had to work like a slave when he was a child. He had to be tough to stay alive"

"I suppose children were forced to leave school at a young age," I commented.

"Angus’s parents were poor and gave him to a farmer; they sold him," said Carmen. "Angus had to work seven days a week from early morning until late at night. He could be beaten if he complained. He lived in a freezing cold building with no toilet or bath and he’d be fed scraps. Britain this century. At least in Indonesia it’s warm and you can bathe in a river."

"Selabintana was cold at night!"

I told Carmen about the judge’s house.

"Maybe he has a rich wife," she said. "Anyway, people say there’s just as much corruption in Britain and Europe as in Indonesia."

"I suppose in the West it’s more cleverly covered up," I said.

23. NEW HOME

Next evening I found Iwan and his granny back home at their shack beside the rubbish tip. Granny, dressed in her usual old shawl and smiling her nearly-toothless grin, looked fit and well. But Iwan was not well. He resembled a famine victim; he appeared to have a fever; mosquitoes, lit by the light from a kerosene lamp, were buzzing around a coin-sized, infected wound on his left calf.

"Why did you go off without your leprosy medicine?" I asked him indignantly.

"I wanted to visit my mum." He was looking down at the ground and sounded as if he was ready for a stretcher.

"But you should have waited till you’d got your next lot of medicine."

"Sorry Mr Kent," said Iwan quietly.

I turned to granny. "Why didn’t you bring Iwan back when he got sick?" I asked.

She grinned sheepishly and said nothing.

"And how did you get the wound on the leg?" I asked Iwan.

"I was playing with some children."

An hour later, Iwan, granny and I presented ourselves to Dr Handoko at Jakarta’s smart Kuningan Medical Centre. A nurse cleaned the leg wound and issued some pills. Dr Handoko decided that Iwan would need to be admitted to a hospital. He phoned the expensive Rasuna Said Hospital to check they had a bed.

"Yes, they can take him," he said. "You’d better get there straight away."

Ten minutes later we were at the Rasuna Said, a tall block with dark marble halls, looking as much like a five star hotel as a hospital. I was beginning to feel rather pleased with myself as I explained to the female receptionist how I was helping Iwan. She asked us to wait in a side corridor. A few minutes later we were approached by a woman who could easily have entered a Miss Indonesia contest; she was long-limbed, dressed in a slim grey suit, and wearing a badge that said ‘public relations’.

"I’m terribly sorry," she said, "but we’re full up tonight. We have no beds available."

"I was told you had a bed," I protested.

"That was a mistake. I’m sorry but the boy will need to go to the leprosy hospital in Bekasi."

"Is it because he’s a poor child wearing sandals?"

"I’m sorry. There is no bed available." She smiled a public relations smile.

"But I was told you had a bed."